Iron Or(e) City – Mine forces small town of Kiruna to move location

With the opening of the new city center, the long-term city transformation will reach one of its biggest milestones this summer. But the highly complex moving project does not come without problems.

by Maren Krämer | 13.06.2022

It is a spring Saturday in the Swedish town of Kiruna, and the streets are nearly empty. Grey clouds and a strong wind make 15 degrees feel like winter. A shop window in the main square reads “Last chance before we relocate our shop”, and the local bank invites people to “join us on the journey to the new centre”.

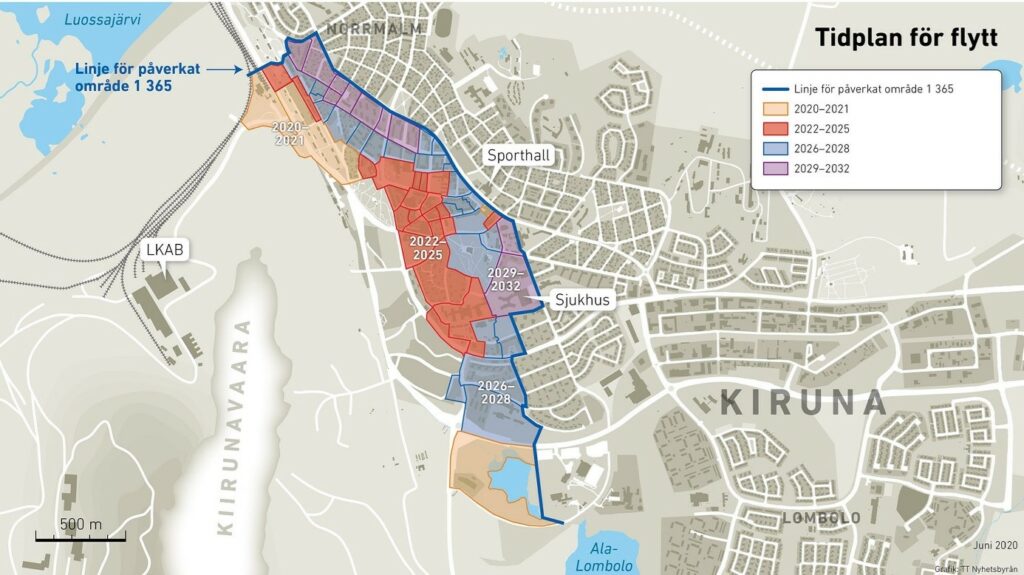

The “new centre” is at the eastern border of current Kiruna, three kilometers away from its old location – and three kilometers away from one of the biggest iron ore mines in the world. As mining has continued in greater depths throughout the years, the ground above has become too unstable to hold the city’s buildings. In 2004, the mining company LKAB announced that parts of Kiruna have to be moved by 2035.

The first houses were demolished in 2018 – and the move has been going on ever since. Red wooden buildings define the image of the Trafikverket area (in orange), where the local train company settled down many years ago. Some of them will be demolished soon, while others can be transported to the new city.

(c) map: LKABThe legal framework is given by the Swedish Minerals Act. LKAB has to compensate any damage created by the mining business. The cost for the whole project is over one billion US-Dollars, including payment for citizen’s housing. About a third of the 18.000 citizens in the town will have to move. Property owners can choose between receiving the market prize plus 25 percent or move to a new house, and tenants can move to the new center with LKAB matching the difference in rent for the first seven years.

Nowadays, the old town feels like it is in a state of waiting. On rare occasions, the square becomes alive again. Like on the day of high school graduation, when teenagers and their families assemble around the churros cart. Or on Sunday afternoon after church service, when dozens of children fill the yard with screams and laughter. Within minutes, they are all gone, packed up in cars and taken to their homes, scattered all across the widespread municipality area of 19.447 m². It is only limited by two giant rock formations – Luossavaara and Kiirunavaara.

The mountains and the mine

LKAB is named after them, and up until today the mining mountains define both the landscape and the whole life of the town. In 1897, LKAB’s managing director Hjalmar Lundbohm decided to build a town for his workers right next to it. Approximately 2500 people work in the mine, and many more are employed with suppliers. “Every family is involved in some way”, explains Gun-Britt Landin Henriksson from the Kiruna Turistcenter. She regularly gives tours through the mine and has been living in Kiruna her whole life. “The city and the mine, they are living in a symbiosis. LKAB relies on the city and the city relies on the mine.”

Job offers from the mine and the local space industry are one of the main reasons why people come to Kiruna. For being such an isolated small town, it is surprisingly diverse as workers come to the city from all over the world. LKAB Employees also can’t complain about the salaries. Working in the mine allows young people to buy cars, houses and go on nice vacations early on. Other employers in the area can hardly keep up.

The relation of Kiruna to the mine might be an explanation for the citizen’s mostly compliant reactions to the move. “I think that people just understand”, Marianne Nordmark, Municipality Communications Officer, says. In 1980, the Ön area close to LKAB had to move because of ground deformation. “So the city transformation has been going on for decades”. The people of Kiruna know about the history of the mine, their grandparents or parents move up north because of it. Local guide Henriksson sometimes compares the mountain and the mining company to a mother:

She provides us with food on the table and a roof above our heads. And we want our mother to live as long as possible. We still want food on our table.”

While Henriksson was born and raised in Kiruna and has a lot of memories connected to the old city, the many citizens that moved here for work are less attached to it.

Fredrik Andersson came to Kiruna to open his jewelry shop back in 2006. Though he appreciates the work others have put into building the town, he isn’t very emotional about the move. “I am now 48 years old and still curious about life. Changes are not always bad”, Andersson makes clear. “But it’s always more difficult when you get older. I see customers that get sad because they want to keep the old things.”

21-year-old Ennock Lufakalyo values the atmosphere of the old city and is glad some buildings can be moved, but he is also looking into the future: “Kiruna was very big in the 50s, and I think it’s going to be big in the two or three years coming.” To him, a change of location means a loss of culture. “But in time, you’re going to get to know the new culture. The generations coming, our generation, is going to take over and we’re going to just focus on the new.”

For young people like Lufakalyo, job opportunities and living space are most important. Due to the move, space for both locals and incoming workers has become rare. The ongoing construction can also cause people to move away. “I had my private house rather close to New City. But when they started to build, it was so dusty everywhere. So we decided to move out”, explains Kiruna-based tour guide Henriksson.

When buildings were created in the areas she usually walked or skied in, she decided to leave for a smaller village nearby. She assumes she is not the only one: “Many with kids, and also elderly people. They moved out just to have the freedom to be very close to nature.” Others leave Kiruna entirely, follow their children to student cities like Stockholm or Uppsala.

On the move

For the people who are staying, a modern new city center is growing rapidly. The chosen area is far enough to be safe from ground deformations. As it is built for the people of Kiruna, their input was considered from the start. Sustainability was another focus, and public transportation will play a much bigger role. In April, the new city hotel welcomed their first guest, and the new commercial center will open its gates on the 01 September. But there is still a lot to be done. Though the new center is connected to the city, those living in the area currently only have access to a bus that goes once an hour after 6 p.m.

Some issues can be solved until September, but there seems to be varying information about the state of the commercial center. According to shop owners, LKAB informed them that the move of their companies will be delayed, possibly until the beginning of next year. As the new commercial area will be right next to the big hotels, being stuck in the old town during the main tourism season could lead to a huge deficit in profits. Like everywhere, there is a growing tendency for online shopping in Kiruna. Tourists who want to buy locally to remember their trips are therefore especially important for the businesses.

LKAB, on the other hand, sticks to their plan to (re)open all shops in September. “Everything is fine, everything is ready”, reassures communications officer Ulrika Huhtaniska. According to her, if there is a delay in the moving process “it’s up to them, they have decided by themselves”.

Lots of questions for local shops

For shop owners, the move is linked to a lot of insecurities either way. While Yuki Fredriksson, CEO of the tourism company Kiruna Guidetur, is happy about LKAB paying for a new building and says it feels like a possibility for a new start, she is also worried: “No one knows how it’s going to be like. Do we lose many customers because of that? What kind of problems are we going to have? No one really knows.”

The fact that LKAB is obligated by law to compensate any damage caused by mining operations also means that they are mainly in charge of the moving logistics. For jewelry store owner Andersson, this means other interests sometimes come second: “They listen to what is important to me, but they concentrate on their own production. That is always first, and then the second part is how should we move this – so we can get the area for our production.”

While the new city center prepares for the big opening, the pit next to the Kiirunavaara mountain is growing and coming closer to the city every day. A big fence is dividing the landscape, what is behind the fence becomes mining area. After the demolition of the first houses, their layout was recreated here using leftover building material.

“It was a reminder for those who had their apartments there, they could walk around a little bit to see well, this is where I lived for 20, 30, 40 years”, remembers Turistcenter employee Henriksson. Now, the area is already fenced in.

The ground that is still accessible was turned into the Gruvstadsparken, the mine city park. Little signs with QR codes show visitors what was once standing there. But it is only a temporary solution. “As soon as this area starts to be dangerous, we know they’re going to fence it”, says Henriksson.

The move is not a permanent solution. Though it saves the town from collapse until 2060, ongoing mining operations are still a base for an unsure future. The area being moved now is affected by a mining level of -1365 meters, but LKAB might go deeper. Test drillings indicate that there is ore at the -2300 metre level. “How will that affect our city? We don’t know yet”, local guide Henriksson says. Huhtaniska from LKAB admits:

“It is impossible to say if we have to move some parts of the city since LKAB has not taken any decisions how to extract the iron ore.”

But she can confirm: “We are continuously researching the iron ore and what we know of there is no ore in proximity of new city center.”

Like all natural resources, even the seemingly endless iron ore body in Kiruna could one day be gone. Tourism has been growing significantly in the last few years, and the clear skies make Kiruna a profitable location for space research. “In a way, we have three legs. Tourism is a strong leg. The space industry is not as strong, but still a leg. But the mine is the strongest one”, tourism expert Henriksson sums it up. Would the others be enough to replace the mine? “I hope that tourism gets big enough”, Guidetur-CEO Fredriksson says. “If we could survive, even when the mine is gone? I hope so.”

Leave a Reply