By Glen Barclay & Oskar Rask Hjorth

While the older generations of Bosnia were busy fighting each other, recent generations have their eyes set on a new battle: countering Nationalism.

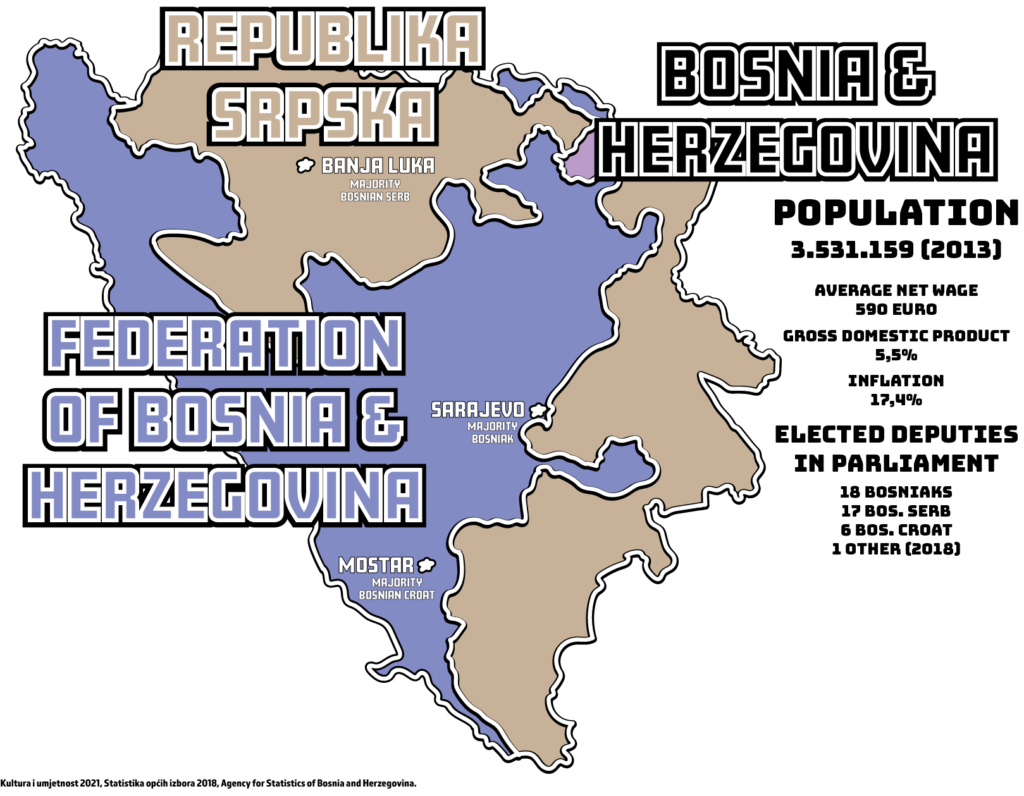

The mountainous, almost landlocked nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is home to several ethno-religious groups, the three largest being Bosniak, Bosnian Serb, and Bosnian Croat.

Today, the country is led by three different presidents, all sworn in at once, each one representing an ethnic majority, and each taking turns to lead the country twice for a period of eight months, one after the other.

A history of violent conflict between the three groups is part of the reason behind the country’s current political system, whose very structure has come to reinforce ethnic division, leading to the current situation of power in politics being driven by nationalist fear mongering and contested narratives based on interpretations of history.

While nationalist politicians feed on ethnic division, broadcasting spiteful narratives, domestic peace-building organisations are working against politicians in power, to mend the divide between the country’s ethnic communities.

Politics in post-conflict Bosnia

Zlakto Jovanovic holds a PhD in history, specialising in nationalism and identity in former Yugoslavia, and currently works as an analyst at The Democracy in Europe Organisation, an organisation devoted to promote participatory democracy in Europe.

“Bosnia and Herzegovina has a unique political structure, where not one but three presidents are all elected at once, to govern the country for four years,” Jovanovic explains.

“One president has to represent the Bosniak ethnic group, another the Bosnian Croats, and the third president elect has to represent the Bosnian Serbs.”

The fact that presidents are elected based on ethnicity, has come to reinforce nationalism in the country, because candidates must appeal to ethnicity to garner votes, and as a result, it has come to dominate the country’s politics. Jovanovic suggests that the way the country’s political system is structured forces politicians to take a nationalist stance to stay in power.

“Milorad Dodik, the current Bosnian Serb president, was viewed as a moderate when he entered the political stage in the nineties, as he had a vision for the Serbian part of Bosnia and Herzegovina to part with the nationalism of that time, even the then Secretary of State of the United States, Madeleine Albright, described Milorad as a positive force in Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

“But with time, Milorad has become more nationalistic, and I would argue, along with other researchers and analysts, that it is the political system which has prompted his nationalistic politics, because for many years the only way to conduct politics in Bosnia has been through nationalism.”

And it’s not just Milorad, the current president of Bosnian Serbs, who conducts nationalist politics. Since the 90’s, every former Bosnian President has portrayed nationalist politics in accordance with their own ethnic group.

“It’s self-reinforcing,” Jovanovic says.

“When one side promotes nationalistic messages, the other side goes on to respond or promote the same type of message. This has also been affecting the country’s leadership, with leaders painting each other as threats.”

But with the result of the recent election in October, it seems the country’s pattern of conducting nationalist politics may dim down, after two of the country’s three elected presidents are the first to not belong to an entirely nationalist party.

Sarajevo

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into cantons. Each Canton is run by elected officials.

Jovanovic explains that politics in the Sarajevo Canton, the canton belonging to the nation’s capital, have been a refreshing force of progressive politics by being more concerned with practical issues rather than history.

”While the local government in Canton Sarajevo have tried to separate politics and history, they have also erected a memorial for some of the Serb victims of the war. The memorial is a big step towards reconciliation, when Bosniak politicians publicly recognise Serbian victims, which is something you would never see in nationalist politics.”

Jessie Barton Hronesova, an expert in Eastern European politics, agrees that the government in Sarajevo is focusing more on practical issues, although she does not believe it comes at the expense of nationalism.

“They are focusing more on the practical issues,” she says.

“Sarajevo has huge issues surrounding pollution, water sanitation, quality of schooling and transport, which have not dramatically improved in the last 15 years.”

Efforts to improve public utility, the availability of parking and daycares, as well as reconciliation between ethnic communities, all increased four years ago, when the current Mayor, Benjamina Karić, was sworn in at 30 years old, becoming the youngest Mayor in the history of the capital.

Barton explains, that “in general in post-conflict states around the world, it’s usually the youth that takes over the peace building role and has more liberal than nationalistic views.”

When Barton first began her research with youth of former Yugoslavia, it was in a period where the fruits of the first post-war period were there – state building, liberalisation, open discourse, media and so on.

“The youth of that time was influenced by that, and they really adopted those views and benefited from civil society projects, international funding, and they travelled a lot.”

“There was huge improvement in Bosnia until around 2006 and then nationalism took over the public space. It was that year that everything kind of froze when the nationalists came back riding their trauma horses.”

The increase in nationalism in politics has resulted in further entrenching ethnic communities, leading to more mono-ethnic communities, and less interaction between different groups.

“Much of today’s generation knows nothing else but these divisions.”

The Perspective of Youth

However it is suggested that outside of the Balkan bubble the ethnic hatred dissipates slightly, away from the nationalistic propaganda portrayed by politicians and media alike.

Abroad Bosniaks greet Serbs or Croats like friends. Sharing food, drinks and even clothes on occasion, should their paths cross on beaches across the Mediterranean, at least according to two Bosnian youth.

“When we meet each other anywhere in the world, we are like family. But here in Bosnia, we are fighting,” says Elma Slabić, a Bosniak, and one of two youth ambassadors to the EU, representing the Western Balkans, alongside her Bosnian Serb friend Šerif Salihović. They are part of the previous generation, which grew up in a fruitful Bosnia.

“For the last two years, I have been a youth ambassador of the Western Balkans, and I have had the opportunity to work with people from Croatia, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia and Montenegro – people from all over the region – and while we are different in many aspects, we have many more similarities than differences,” insists Salihović.

He adds that “Sarajevo is a place where a lot of cultures have met throughout history and we forget that. Right now it is the same, three different cultures who are very close and very similar living here, it’s the destiny of Bosnia to always be multicultural. If you walk through the old town you can see a synagogue, an orthodox church, a mosque, in almost every small town in Bosnia you can see it.”

The youth impression of the generations who preceded them presents a complete lack of belief in the political system, whilst they don’t hanker for Liberalism, the faith in a Nationalist system where votes can be bought by politicians fails to resonate fully with many throughout society.

“My parents didn’t vote – they don’t believe their vote can change anything; they have the idea that a vote can be bought for a cup of coffee,” admits Slabić.

The political spin machine along with their media accomplices attempt to widen the ethnic divisions through nationalist propaganda in the lead up to elections. By driving a wedge in between factions those in power guarantee their political safety, promoting highly nationalist agendas in order to cause mistrust within the populace which forces them to return to the ‘safety’ of their communities. With the voting system only compounding the differences of ethnicity in its structure.

“I hate him,” as she nudges Salihović in the ribs, “but only in the weeks leading up to election day,” Slabić says jokingly.

“People outside of Bosnia often don’t know about good examples of how we live life together, only the bad examples that are promoted by the media,” Salihović states.

“We live together and we respect each other, we don’t have problems between ethnicities, but from the political perspective, the source of almost half of the problems are the results of war, which gives some power to the governments in Zagreb & Belgrade who can influence a lot of the activities here – most of which are against the development of this country, this society because they want to be leaders within the regions.”

The consensus of the Sarajevo youth points in a collaborative direction, where the embracing of one another’s cultures is common practice.

“Respect others’ religion and love yours. I go to church on Christmas Eve because of the energy, we don’t believe in the same God, but we believe in being good. When my family celebrates the muslim holiday Bayram, my friends come to my mother to help iron the shirts and eat Baklava, but something happens in politics, and we forget all this,” Slabić says.

There is a long way to go and many battles to face but the shoots of ethnic integration throughout Bosnia’s future makers are present despite the best efforts of nationalism.

An uncertain future?

Efforts to counteract the growing rift of ethnic tensions can be seen throughout the middle ground of Bosnia, the relative neutral zone, where the toxicity of nationalism is not as rife, with the youth the main targets of intervention.

These movements face the challenge of overcoming the hatred and division that nationalism breeds within the country.

Whilst there are some who would actively keep to their singular ethnic communities, an ever growing group are fighting to break down the divisions built on nationalistic tendencies.

Originally established as an organisation to educate youths on dialogue between different religions, and help children in dire situations, Youth for Peace has grown into one of the cornerstones of ethnic education and integration within Bosnia.

Their goal is to create sustainable coexistence amongst youngsters who have had little to no exposure within alternate ethnic communities and educate them in a way that spreads the message of peace.

The organisation’s president Daniel Eror, who has been working with the project for 16 years, believes the lack of integration between ethnicities at a young age helps build these divisions.

”Imagine that you are twenty years old and have been brought up in a monoethnic community with the idea of having to keep strictly to your own group to stay safe. Our role is to step in with a person who has had the same upbringing, but in a different community, and you will both see that you have been fooled.”

Project coordinator and mentor Samira Baručija supports this idea and suggests the division is furthered by the encouragement of national identities.

“It’s much easier to believe hateful messages about other groups, when you have never had any interaction with them.”

Unsurprisingly, the political system built on aligning the populace with their ‘own’ people, is unsympathetic in their support for such operations with Eror suggesting a culture of ‘systematically designed resistance,’ within education.

“The system keeps those young people ‘safe’ from us, if you keep them closed and segregated, away from our narrative, then they are under your control. If we would come there then we would challenge their minds, they would start thinking and they might start thinking differently than the ruling narrative.”

But this is not a process that can immediately produce results, suggests Baručija, with the stigma of interacting with other groups still prevalent in rural communities in comparison to Sarajevo.

“We have had participants who were great in our activities, and really showed a desire to change things, but once they went back to their communities, we would see Facebook posts that were completely opposite to what they had shared with us. And that’s that pressure – it’s not easy to go back to your community and change things.”

Establishing these new ideas amongst young people is a rewarding process when it prospers but it does take its toll.

“Peace-building is heavy, it’s emotional, there is blood, sweat and tears because people come with different stories.. but every community, no matter where you go, needs peace-building and that’s our role.”