How do you fancy a grasshopper-taco, cricket carbonara or mealworm bolognese? These foods might seem startling and scary at once. But prepare yourselves. Very soon they could substitute what we know as animal protein. New sustainable choices are essential to fight climate change. But people in western countries have a deep-rooted cultural barrier to not associate insects with human consumption. That is the problem we are facing.

By Salma El Ashmawy and Marie Louise Gimm

The facts are very clear. Insects are basically a superfood. They can boost our immune system, have lots of nutritional benefits like high levels of protein, minerals including iron, calcium, zinc, and magnesium, and they are rich in unsaturated fat as well as amino acids.

These facts were documented in a book by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in 2013. Also, the greenhouse gas emissions are close to 100 times less than traditional beef. Meaning one kilogram of edible insects emit one percent of the emissions one kilogram of beef do. So, what is not to like?

We need new protein sources. Fighting climate change is one reason, but also to help combat the growing world population.

By 2050 we will reach nearly 10 billion bellies to satisfy in the world according to the World Economic Forum, which legitimizes the demand for new protein sources. But somehow, we need to break the cultural barrier to actually make people open minded towards eating insects.

One starting point could be the education system, Danish expert Lars-Henrik Lau Heckmann suggests. He has a Ph.D. in biology and is head of business development at Better Insect Solutions. He explains how many children up to a certain age are quite open to try new things.

They do not have any prejudice regarding what is food and what is not. So, if they learn to cook with insects from a young age, it becomes natural to them, and it becomes naturally integrated as part of their food culture.

Basically, what we need to do is exploit children’s curiosity, and use this eagerness to change the narrative. The idea is starting to gain more attention; several teachers in Denmark have implemented project weeks focusing on the tiny crawling animal.

One of them is nature science teacher, Rasmus Brinkmann Jespersen, from Ellidshoej Elementary School in Northern Jutland. Two years ago, he had his first-time experiencing eating mealworms and crickets together with his 4th and 5th graders. He was pleasantly surprised by the taste, and since then the insects and him have grown together, meaning the insects have become part of him as a teacher now.

“The kids know I have them, and they know that when they enter 4th grade, they have to cook with them,” he says.

However, when Jespersen initially presented the insect-project-week two years ago the children were caught by surprise. He explains how the school is surrounded by a lot of fields and trees, so the children have always been out digging the ground and talking about insects has never been a stranger to them. The relationship was natural so to say.

“But when I told them that we had to cook and eat them, they were a bit scared. But they still managed to keep an open mind and try it” he remembers.

It put a smile on his face seeing the bond being formed between the students and insects. Watching the kids nurse and feed the insects, but also being willing to eat them in the end. Basically, the whole week was a success. Afterwards he has only received positive feedback from the children’s parents. And when asked whether no negative comments from parents had occurred, Jespersen answers very straight.

“No,” he says without any hesitation.

The problem lies with the adults

Adults are often the ones hesitant to try new things. Having no negative comments from parents does not equal that grown-ups are as open minded as the children.

Senior lecturer at University College Lillebaelt, Majbritt Pless, has lots of experience with this non-open mindset. She educates future schoolteachers in home economics and was part of the project Taste for Life that uses food as a driving force for learning. It was ongoing since 2014 but came to an end last year.

During the project she developed school material and had the idea to make eating insects part of the curriculum. The idea had emerged from a student of hers a few years earlier in a school kitchen for a final exam.

“I remember that exam in home economics. A student had cooked insects for me and the censor to taste. I had no problem with it, but the censor did. Normally we taste test whatever the students cook, but the censor refused” she explains.

Pless had many thoughts when developing the material, but she was certain she wanted to make it a success. It had to be something familiar. For instance, crisp bread made with insect flour and chocolate chip cookies made with whole mealworms. She did not want it to be an unfamiliar food topic and an unfamiliar dish at the same time.

Pless also had the same experience with the parents as Jespersen did. No parents were negative towards the idea of letting their children cook with insects and taste them. However, they did not want to taste it themselves.

This is the problem she sees most of the time with adults. They reflect and are much more skeptical due to the cultural barrier in western countries. A cultural barrier that only makes 10,3 percent of people in Europe willing to replace traditional meat with insects. That is at least what a study shows from 2020 by the European Consumer Organization. In comparison around 2 billion non-western people eat insects on a regular basis, which are approximately 25 percent of the world population.

Sometimes it surprises Pless just how unwilling adults are, because they are the ones who pass down their habits to the next generation – children. Just last week she had a continuing education course with some home economics teachers. At the course a nature science teacher had fried up some mealworms for them to taste, and almost no one of the teachers would try.

“We are talking about grown up home economics teachers, who are already employed by the Danish public school” she tells worryingly.

A sustainable and no waste production

Sustainable and climate neutral farming is slowly becoming the new norm. And although fried mealworms are not for everyone to like, a woman settled down in a yellow farm in the far countryside of Jutland makes a living from them. Here she is born and raised. Her name is Dorte Svenstrup, and now she is general manager at Heimdal Entofarm – a business that produces and sells more mealworms in a year than imaginable.

Originally the farm had traditional agriculture for more than 100 years, but when Svenstrup took over she wanted to change that. She felt sad to hear about all the downsides to traditional farming with high greenhouse gas emissions. Sustainability was her way to go, and now she has achieved that to a large extent.

Today 12 small cardboard boxes make up the whole foundation of the production site. In these boxes mom and dad crickets are crawling, sizzling, and reproducing new mealworms for the dinner table. Svenstrup is proud of what she has accomplished.

“We don’t let out CO2, we don’t use any water, we only feed with leftovers, and we don’t produce any leftover things ourselves. We clean up the world, so to speak,” she states.

At Heimdal Entofarm they are also keen on the idea to educate children and young adults on sustainable proteins. They do collaborations and go out to schools, young children and gymnasiums to share pictures from the production site, and explain what they do and why they do it. Always bringing along samples to taste.

From when she started the journey six years ago till now a lot has changed regarding the perception of people.

“Every year I feel that people know more and are more interested in what we have. They are not scared anymore. The first years were like ‘what’s that?’ and now they know it and enjoy it” she says.

She also sees an increase in both sales and the web shop, which is where most of the products are sold. So, the future looks good, and now a new product is waiting in line to be released. A possible bestseller product: a burger patty made from 50 % crushed mealworms and 50 % vegetables.

Everything is working out quite well for Svenstrup and now her focus is on bringing down the price, so the products can compete with other products on the market.

Heckmann agrees. For him the price is the first challenge to get the consumers on board. Insects need to be available at an economically viable price. That needs to be settled as a first milestone, because consumers might be willing to pay 20 to 30 percent more, but nothing more than that he specifies.

Sustainability only works if it is tasty

Tasty and sustainable food is what keeps us coming back for more. Heckmann mentions the importance of good taste, because unless you can put sustainability into something tasty and delicious people do not want it.

Taste and texture are the issues here. Both vary a lot depending on the specific insect, so we need someone who can teach us all the tips and tricks to cook it in a nice way. The easiest way to accomplish that is to have more chefs working with it. The gastronomic sector simply needs to contribute and make insects a hyped interesting ingredient to use in our food. That is Heckmann’s main point.

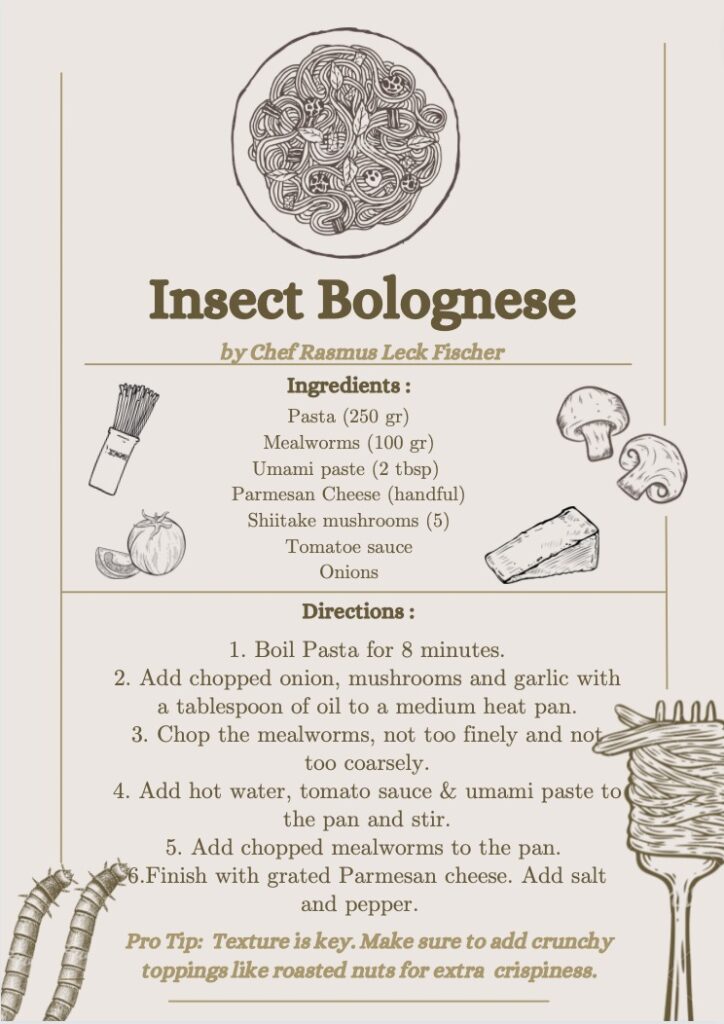

Several chefs have already put a lot of effort into experimenting with the texture and taste of insects, and one of them is Rasmus Leck Fischer, head chef at Gastronomic Innovation in Copenhagen. He has written several cookbooks including “Insectivore” that is dedicated to cooking with the crawling species.

He agrees with Heckmann. It is not about eating insects; it is about whether they taste good or not. And cooking with insects is completely different from cooking with traditional meat. You can sort of compare it to cooking with the texture of popcorn.

“You have all the issues with the kernels, the chewiness, the getting stuck in the teeth and texture problems” he says.

Even though many people are still hesitant to eat insects, the chef is convinced it makes sense to start cooking with them now. It takes a lot of time to conquer the ingredient – and expertise is needed. If not for now, then for later.

According to Fischer it also makes a lot of sense to teach children from a young age to cook with insects, and he has done a few workshops himself which he loved. And with the schools already looking at environmental topics, the chef thinks it would be a natural thing to also teach children about food, future, and sustainability as part of the curriculum. He even believes that if you try eating an insect in school the body will remember and make it less scary later in life to try again. But you should not just serve up whatever, is his advice for teachers.

“I would say that the easy part is introducing the insects. Talking about them and showing sustainability. You can definitely do that. The thing you should be aware of, is that the samples you serve should not be a whole bag of freeze-dried mealworms that you just throw on the table. You have to consider what you are serving, because it is the first time for most of the kids, and if it is a bad time you lose in advance. So, spend a little extra time to make nice samples that the kids remember in a positive way” he says.

Perhaps make it crunchy, salty, or funny. That is a relatively easy way to succeed and then the kids will come back for more.

The future is impossible to tell

Whether implementing insect-satiated curriculums in schools is going to change the narrative and break the cultural barrier remains unknown. At Heimdal Entofarm they have a very positive outlook to the future, and the same applies for Heckmann. In ten years, he believes we have come a long way from where we are now. But not everyone has a positive outlook as they both do.

Senior lecturer Pless does not believe in eating insects – at least not to a great extent. Initially when she developed the teaching materials in Taste for Life, she hoped it would make a difference in the future. But too many years have passed without much progress in the area, and we are currently in the future she hoped to change years ago.

“Of course, I can’t be sure, but I believe it is too expensive, unavailable and the cultural barrier is too big to overcome. The progress is simply too slow,” she expresses.

Nevertheless, children still show curiosity and interest to study the world of insects, and cooking with them has been a success in schools that have welcomed the idea. Nature science teacher Jespersen is an example that you can break a barrier and make young school children expect and accept cooking with insects, regardless of what their diet might be in future.

Another thing to be aware of which could indicate a more positive future towards insect consumption, is the legislation barrier that has now been lifted. A regulation known as ‘novel food’ has been a big hindrance for insect producers.

Basically, it has prevented all foods that we have not eaten in significant amounts before May 15, 1997, from being open to the market. Pre-market approval has been the only way, meaning intense documentation to secure consumer safety. And recently the European Commission has approved several insects for food consumption.

Heckmann informs that there are now seven different ways of applying insects as food in Europe, which is based on primarily four different species. One species of crickets, one of grasshoppers and two types of mealworms. So, it is starting to gain traction again due to legislative opportunities to go to market, which for a couple of years was a gray zone area.

Svenstrup at Heimdal Entofarm has also experienced more requests from foreign countries since the breakthrough.

So, whether the western-cultural barrier is too big to overcome as Pless anticipates, we have to wait and see. But nailing good taste and making delicious food that can speak for itself is the best tool we have in the toolbox.

“In the end great food is what will persuade people to eat it,” Chef Fischer finishes by saying.