Despite a recent spike in tensions in Serbia and Kosovo, community members and groups are continuing to work towards a better future.

By Ernst Calitz and Rachel Jackson

Since the war in 1999, Serbia and Kosovo have been at odds. Nearly 24 years later, the people of the two opposing nations seemingly want to move on and reconcile, but the governments they live under hinder the efforts.

A recent spike in political tensions between Pristina and Belgrade made waves in foreign and local press earlier this year. The spike in political tensions came as a result of the Kosovar government’s announcement that individuals who hold Serbian ID documents and licence plates would need to replace them with Kosovar documents or face legal penalties. This announcement was followed by mass protests in late July and early August.

The two countries reached an agreement in November, with Josep Borrell, the EU’s foreign policy chief, announcing that “chief negotiators of Kosovo and Serbia under EU facilitation have agreed on measures to avoid further escalation”.

Although the ID document and licence plate negotiations are on ice for the time being, the two governments still remain at odds politically.

Shqipron Xhema, a political scientist and journalist based near Kosovo’s capital, Pristina, argued that “the problem is the governments cannot agree on anything, and this is a problem that is reflected in the people”.

Rebuilding community ties in Mitrovica, Kosovo

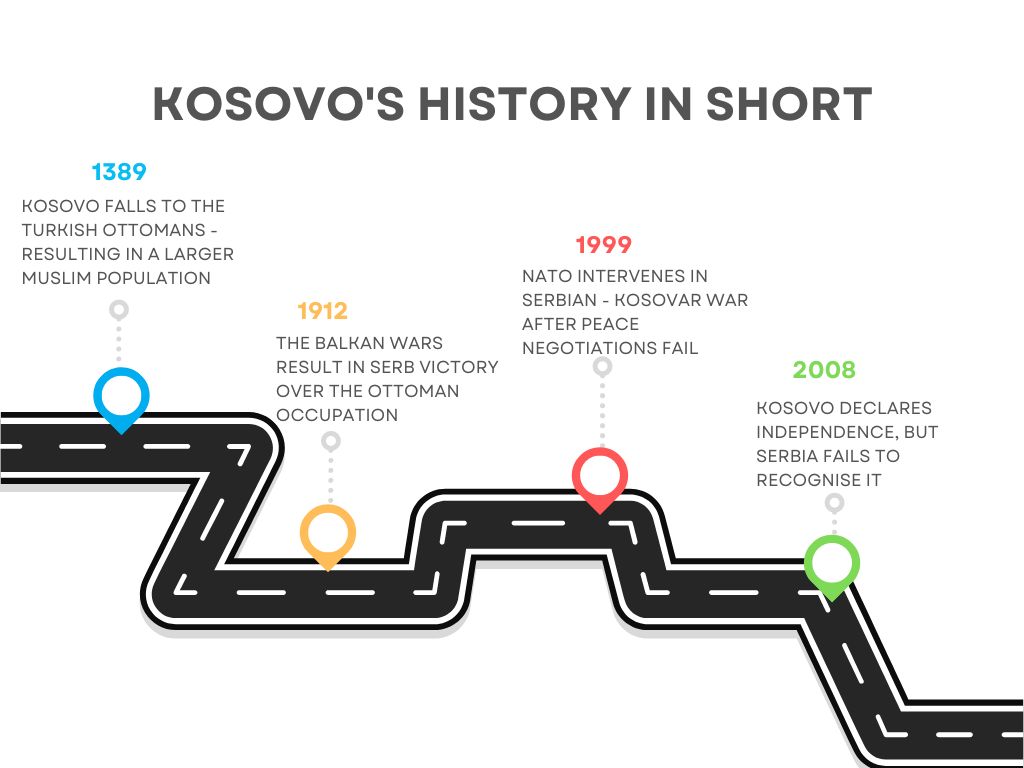

Kosovo declared independence in 2008, but Serbia along with 5 other EU member states still fail to recognise its sovereignty. The small landlocked country is predominantly ethnic Albanian with a Serb population making up only 6 and a half percent of its 1.8 million-strong population.

Mitrovica, a shell of a former prosperous city, lies roughly 50 km from the Kosovar-Serbian border and is a stark reminder of the two opposing nations’ stubbornness. The northern Serbian district is segregated from the city’s ethnic Albanian south. The divide is cemented by a bridge that separates the two parts and is under constant patrol by NATO agents and local authorities – allowing no cars to cross.

A mere 100 metres beyond the blockaded bridge are streets filled with festive-lit coffee shops, bars, and restaurants – a sharp contrast. This is the reality that many ethnic Serbs and Albanians face in Serbia and Kosovo as they are trying to move on from the 1999 war. However, they remain stuck in the middle of two governments who seldom budge at the negotiation table.

South of the bridge in Mitrovica lies Community Building Mitrovica (CBM), an organisation that aims to facilitate dialogue and build relationships between ethnic Serbs and Albanians in the region.

“Local communities are fed up with the ‘stand-by’ or ‘standstill’ situation while the conflict has ended over 23 years ago” said Nemanja Nestorovic, the deputy director of CBM

“It used to be a city full of engineers, rock music, and culture. Now this image is transformed into something else, mostly something negative. Now it only gets attention in the media when there is conflict on the bridge or inter-ethnic tensions.”

The organisation brings members of the respective communities together through a myriad of projects that include the local youth, women and young professionals.

One of these projects was a coffee festival that was hosted on the divisive bridge.

“We tried to reshape and remodel the image that the bridge has into something that brings people together and not a place of division,” the deputy director said.

The festival allowed many local coffee shop owners and people from both sides to interact, network and experience their unique coffee cultures with each other – an opportunity that many of them would never have had.

“The governments do not have the desire to work on reconciliation to its fullest extent. Although they have political statements that say differently – in reality, this is not the case,” Nemanja added.

(By Ernst Calitz)

The organisation emphasises the necessity of providing a platform for local youth to come together and interact. Many of the young inhabitants of the city live in a bubble where they are surrounded by people from the same ethnic background, with little to no interaction with other ethnic groups in the region. The youth are left to form opinions on the other ethnic groups through the negative news spread about them.

“They hate each other before they even get to meet,” said Nemanja.

Programs hosted by CBM such as a multi-ethnic band, composed of ethnic Serbs and Albanians, provide the youths an opportunity to break down these barriers.

“They are reluctant to interact in the beginning, but throughout the programs you see them open up and they realise that they share more similarities than differences – the same taste in music, the same fears, the same dreams and they see that they are not that scary,” he said.

CBM places a large emphasis on bringing the youth together from both sides of the bridge, because many of them can act as much-needed agents of change in their communities.

Nemanja said that all of these projects are the group’s modest way of contributing to the goal, but “the rest has to come from the government, both on a regional and national level” – a prospect that seems to be far off into the future.

What Do The Tensions Look Like?

In Belgrade, Serbia’s capital and nearly 550 km north of Mitrovica and Kosovo, one would not come to think that the two governments are in a political stalemate, as the city does not differ greatly from its other European contemporaries.

Many Serbs and Kosovar-Albanians are moving to Belgrade for employment and business opportunities. Tamara Kukić, a 31-year-old hairdresser, and geography and vexillology enthusiast in Belgrade, finds herself in a unique middle ground between the ethnic tension due to her mixed Serbian and Albanian heritage.

“It is becoming a trend for both communities to work together, especially in the bigger cities,” she said.

She was initially discouraged from disclosing her heritage in the Serbian capital due to fears of discrimination. When she was 25 she decided to openly embrace her Albanian roots.

“Not many people have such an honour of having mixed origins,” Tamara added with pride.

In a rather jovial tone, she said that she very rarely, if ever, experiences any form of discrimination for being half Albanian – on the contrary people tend to be rather pleasantly surprised.

“There is no reason for me to be afraid, people are trying to move forward and forget about crimes, wars, and everything. The media and governments are the only sources of bad news,” she said.

She shared her frustrations about the media portrayal of the tensions between the two countries. Adding that local and foreign press projected a false image of what the situation looks like on the ground.

“The media is the one to blame for spreading the bad propaganda about it,” she said in reference to the build-up of ethnic tensions.

Tamara cautioned people against blindly accepting the way the media portrays the disputes stating that “people should just ignore the media, false propaganda and the government”.

Shqepron agrees that “people are easily manipulated, and this is particularly a problem in the media”.

However, he argues that “it’s a problematic situation because local and international media don’t know what’s going on behind the curtains, we only know what they tell us”.

It therefore becomes even more difficult for the press to portray an accurate image.

Tamara’s Albanian grandfather moved from Belgrade to Pristina, the Kosovar capital, in 1999 after the NATO bombings of the city. She added that even when visiting her grandfather in 2018, she still felt welcomed by the people: “I did not experience any side eyes or anything for being half-Serbian in Kosovo – people don’t really mind” – a testament that the people in both countries wanted to move on from the 1999 war, despite the media portrayal.

Tamara explained that she still vividly remembers the war. Recalling memories of her being overcome with panic in a bomb shelter as an 8-year-old, but being sent home by her grandmother because she was unnerving the other kids.

“If it was meant to be, it was meant to be” her grandmother said – referring to her house getting hit by NATO bombing.

“If they weren’t Albanian they would be something else. The government is just looking for something to blame for the country’s situation. They could have been Bulgarians or Hungarians or Bosnians. The Albanians are the easiest ones to blame, because the conflict happened most recently,” she said while mentioning the governments’ ongoing tensions with one another.

Despite this, Tamara is hopeful that the two sides will come to an agreement sooner or later, calling it “a question of time”.

She believes that civil organisations such as CBM and the K-Town group can play a role in uniting the two ethnic groups, but “they need to louden their voices in order to be heard”.

Using Art to Create Better Community Ties in Kosjeric, Serbia

A small town in western Serbia is paving the way for a more accepting and tolerant future. Kosjeric is located in the Zlatibor District of Serbia, nestled between mountain ranges and river valleys. The town itself has a population of approximately 4000 people, while the municipality is home to 12,000 people.

Kosjeric is a homogenous community; the population is 99.5% ethnic Serb. Homogenous communities can run the risk of becoming narrow-minded, but this is not the case in Kosjeric. The town has become a catalyst for social change, and at the heart of this movement is the K-Town Group. The Group began informally in 1996, with the goal the affirmation of arts and culture, and the protection and the improvement of human rights.

Predrag Diković is one of the group’s founding members. He grew up in Kosjeric but now lives in Belgrade with his family, where he works as a lawyer. Diković visits Kosjeric most weekends to see friends and family, and to remain active in the K-Town Group. While the Group does not focus on Serbian and Albanian relations, he believes community groups play an important role in fostering better dialogue.

“We promote equality and friendship between people,” he said. “That is an answer on how we can work together, to have some action together in a global way.”

Community groups are able to have a bigger impact in smaller communities than in large cities, according to Predrag. It is easier for them to create a more open-minded community in Kosjeric than it is for community groups in larger cities such as Belgrade.

“We know each other personally. We spend time with each other, we know about families, kids, studies and travelling. I like to say that we are like a huge family,” he said.

The K-Town Group has completed a number of projects in the past 20 years. One of the most prominent projects is the International Art Camp. The Art Camp was established in collaboration with other community groups in Kosjeric and Belgrade.

Accommodation for participants was provided at the houses of local families, which enabled participants to get to know members of the community and vice versa. The International Art Camp has had a visible impact on the community, which can be seen in the artwork displayed across the town. It is also visible in people’s attitudes, and new relationships that have been created.

“I remember when we started the international art camp, a lot of people from Kosjeric did not feel connected with anybody from abroad,” he said.

Many friendships have been established at the International Art Camp. There have even been marriages and children born. Diković has had the opportunity to travel abroad and he said the art camp has opened similar doors for people in Kosjeric.

“We want to bring people from abroad to Kosjeric to see that you guys are not something strange, you are people like us, and if we spend some time drinking, talking, going hiking, doing some workshops about art, after that, you and I will become the richest people,” he said.

Artwork from the camps can be seen throughout the town. Murals are painted on walls across buildings, fences and on the local school. Predrag showed us one of the first murals that was painted in Kosjeric from the art camp. Featured in the artwork are members of the camp from all over the world. It is a creative reminder of Kosjeric’s international ties.

Predrag said he does not believe the Serbian Government should recognise Kosovo as independent. The reasons he cited were Kosovo’s historical significance to Serbia and the Kosovar Government’s discrimination of Serbian minorities in Kosovo. For example, Kosovo is home to one of the oldest and most significant Serbian Orthodx Monasteries, the Gracanica Monastery.

But most importantly to him, he believes that the Governments need to focus on fixing problems at a grassroots level before they can discuss politics.

“My opinion is that the focus must be on the people, not a global story about war,” he said. “I would be satisfied that people from Mitrovica can cross that bridge between the south and north part of town to have everything in the shops, the opportunity to go to the theatre and to travel without a visa.”

“When we’ve got that standard, we can discuss independence.”

What Now?

When asked about his predictions for the future, Shqepron Xhema said that “anything can happen” considering the nature of the dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo in the last couple of years.

Shqepron is hopeful that Serbia will recognise Kosovo’s independence under the recent Franco German plan established to improve the countries’ relations. He believes civil and political issues will be resolved more efficiently if Serbia recognises Kosovo.

“It is for the greater good if we accept each other as independent countries and we can continue to fight our problems and to try and resolve them so that we don’t have any problems and issues with each other as people,” he said.

The Franco-German pact is based on a formal bilateral Treaty strengthening the links between France and Germany in terms of security and diplomacy. Their Kosovo-Serbia plan has been rumoured since September of this year, and the proposal has now been confirmed by officials in Pristina and Belgrade. However, its details have not been officially published.

In an article published in November of this year, Euractiv claimed to have obtained a copy of the proposal, which is detailed in nine articles. The third article hints at a future requirement of Serbia to recognise Kosovo as independent:

“They reaffirm the inviolability now and in the future of the frontier/boundary existing between them and undertake fully to respect each other’s territorial integrity,” it stated.

Shqepron said that If the Serbia and Kosovo Governments were to sign an agreement, tensions would likely flare again.

“We understand that if this agreement is going to be signed by Serbia and Kosovo it is going to hurt both sides,” he said. “It is going to be hurtful because after a war and after this many problems, the Governments have to let something go by.”

Local elections in the Serb-majority municipalities of Kosovo are scheduled for 18 December, which has caused another flare in tensions this month. The main Serb-political party said it would boycott the elections, and Serbs have erupted in protest. Hundreds of ethnic Serbs have set up barricades and blocked the two main border crossings between Serbia and Kosovo, with reported explosions and shootings.

Despite the efforts of those who wish to reconcile, the road towards peace is long for Serbia and Kosovo.