by Sigurd Skjoldaa Kempf and Dominique Nash

Mobile devices sold in the EU must use a common charger in 2024. What could it mean for you as a consumer, business, the environment, and innovation?

In 2024, all mobile devices sold in the EU must use a common charger.

Text and Graphics By Sigurd Skjoldaa Kempf and Dominique Nash

After a stressful morning, you arrive to work drenched in sweat, only to discover that you’ve left your multiple chargers at home. With your phone and laptop running dangerously low, getting work done seems impossible.

Luckily, your colleague has a charger that could work with your laptop but not one that works with your phone.

Last week, the European Union passed legislation that aims to leave this problem in the past.

“We want to make it easier for consumers to charge their devices and avoid the waste that comes with having too many different chargers,” said Sonya Godspodinova, a spokesperson for the European Union Commission. Starting in 2024, phones sold in the EU must use one common charger. Other devices, such as laptops, will be affected in the coming years.

On average, homes in the EU have three chargers for mobile devices. However, one out of three isn’t used regularly, leaving valuable resources on the table.

Unused chargers amount to 11.000 tons of waste per year. By adopting the common charger, the amount of waste will decrease by approximately 9 percent, according to a study performed by Ipsos Mori in 2021.

Based on the same study, the EU estimates it will help save consumers 250 million EUR a year on unnecessary charger purchases.

An Imperfect Solution

However, the (new) standard, known as USB-C, comes with a host of problems, argues Rene Ritchie, a leading tech industry analyst.

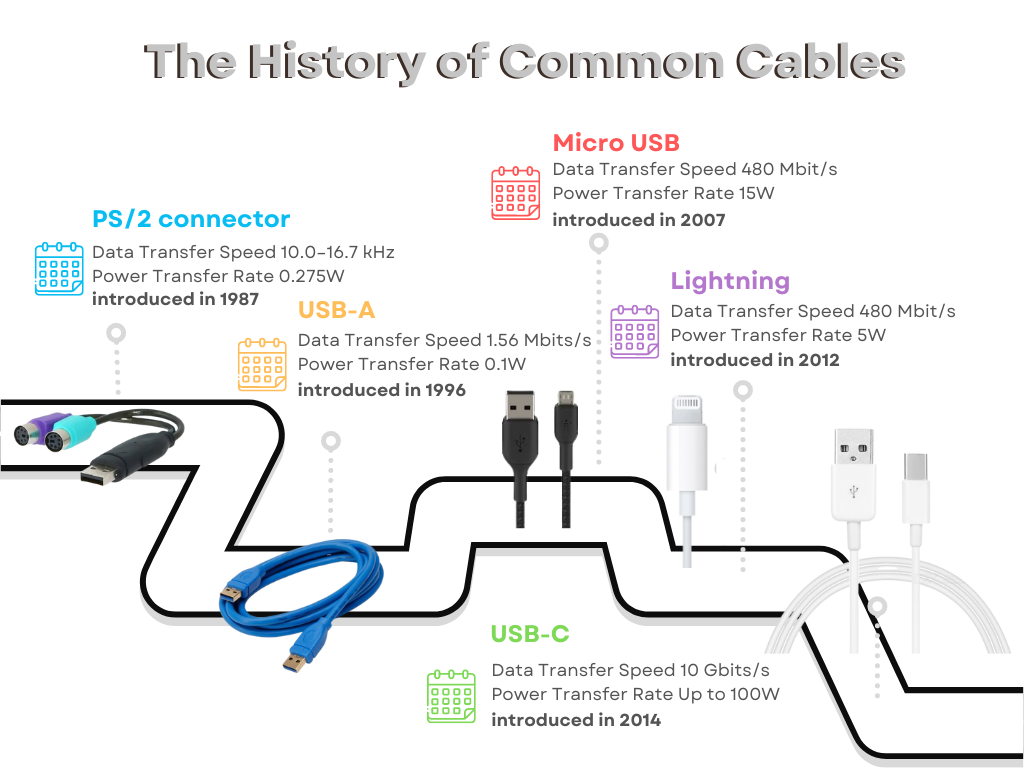

“USB-C was released in 2014. Eight years is a long time in the tech world where there’s always something new, bigger, and better on the horizon.”

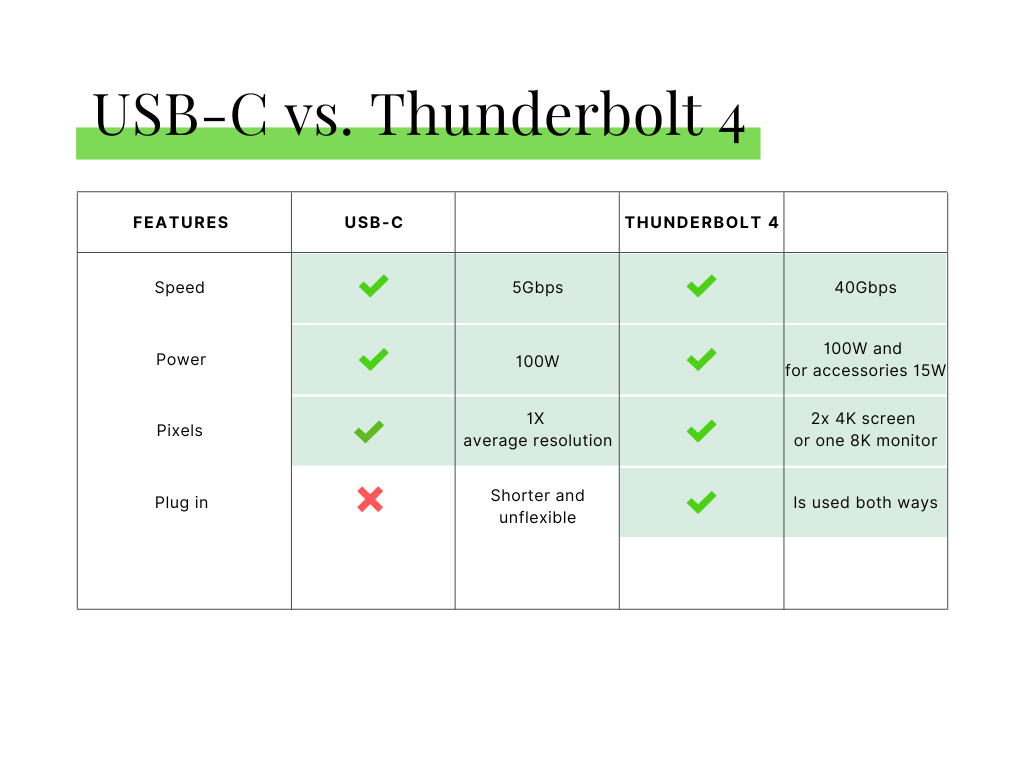

Ritchie explains that while USB-C refers to the physical design and look of the plug, it doesn’t say much about the cables’ specifications and technology.

“The cables look pretty similar, but there are several variations that change often. They vary significantly in what they can and can’t do. Some charge fast, and some charge slowly. Some transfer an image signal, while others don’t. Some cables transfer data 40 times faster than others. The fastest is called Thunderbolt. The slowest cables are stuck at the speed which became the norm 22 years ago.”

He argues that that is part of the problem of making it easier to understand for consumers.

We met Maria, a 45-year-old woman from Spain, visiting the bustling Warandepark in downtown Brussels. She suggested that colors could help identify what each cable does.

“Then, when you see a blue cable, you wouldn’t have to think about it. You would just know it works. I can’t tell much of a difference as it is now.”

Dominik, a 44-year-old man, looks forward to the change.

“I have many different cables at home, and it’s very annoying. I have to get close to see the difference. It’s a waste of time.”

The Smart and Well-Informed Consumer

“When we work on initiatives like this, we go at it from the perspective of the ‘smart and well-informed consumer,’” Gospodinova explains.

We expect a certain level of competence from the consumer in knowing what the cable can do. If you borrow a friend’s cable, we can expect one of you to know. If you don’t know, you can still try.”

Manufacturers must clearly label their products on the packaging in an easy-to-understand way. But, according to Anaïs Michel, a professor of EU law at KU Leuven in Belgium, the Commission could be expecting too much when it comes to consumer knowledge.

“In the past, the EU Commission has been criticized by experts in consumer behavior for its expectations towards the average consumer.”

An analysis of studies by Michel’s colleague Anne-Lise Sibony found that the average consumer might be more overwhelmed, distracted, and impatient than the EU Commission thinks.

In her analysis, Anne-Lise Sibony argues that legal systems often assume that average consumers can rationally make good, required decisions.

The Industry Wants to Decide

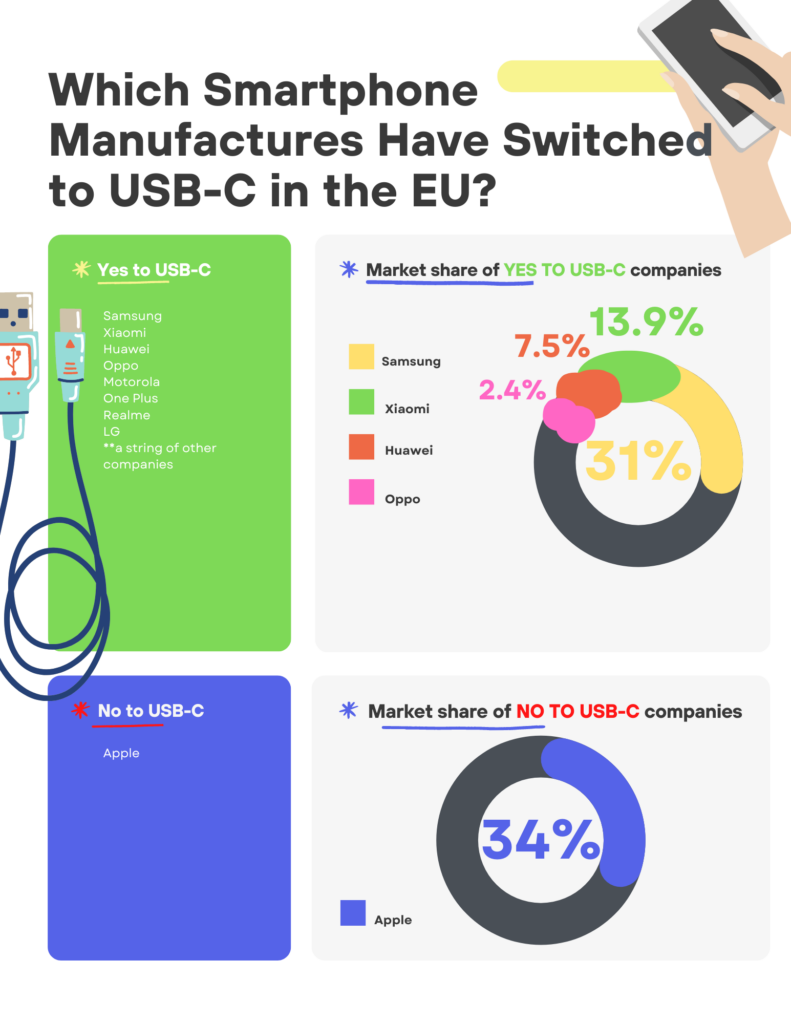

While the EU Commission is intervening to make charging easier for consumers, parts of the industry want to decide for themselves.

DigitalEurope, a lobbying organization representing more than 36.000 digital businesses in the EU, has criticized the approach. They argue that disrupting the ongoing transformation toward USB-C will mark the unfortunate end to a successful and voluntary approach.

In 2009, a voluntary agreement was signed by many of the major companies dealing with charging solutions in the EU. Since then, the number of different chargers has changed from 30 to three.

In other words, the industry got 90 percent of the way to a common charger before the EU Commission intervened.

“It’s always the first priority of the Commission to let the industry decide. But, when a solution isn’t found in the industry, the regulation comes in.

We need to regulate to a minimum and try to do it as little as possible. But, when we see that there is still an outstanding milestone that could have an important impact on the market, consumers, the economy, and the environment, we feel prompted to do it. It’s something we believe is worth pursuing.”

Sonya Gospodinova, the EU Commission.

Greg Joswiak, Senior Vice President of Worldwide Marketing at Apple, disagrees.

“I don’t mind governments telling us what they want to accomplish, but we have smart engineers that figure out the best way to accomplish those things technically.

In the past, we figured out how to make hearing aid compatibility work on phones. Before, for years and years, it didn’t work. But the industry had to follow strict guidelines anyway. Today, our way is the industry standard,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

While DigitalEurope disagrees with the outcome, the organization said it appreciated the opportunity to provide feedback to the EU Commission before deciding how to intervene.

A Big Incentive For Companies

Manuele Citi, an expert on EU policy and economic regulation teaching at Copenhagen Business School, explains that, sometimes, regulation is needed to get things across the finish line.

“It’s a positive development for consumers because it should be more convenient, and waste is limited.

The EU is the biggest market in the World. The only reason it can change a standard, even for international companies outside of the EU, is its size. With 500 million consumers in the EU, the market is very attractive for companies.

It makes sense to have the same standards across different markets because that makes it more efficient for companies and brings down costs,” he explains.

Working Together Across Borders

“It’s up to each EU member state to enforce this change in its national law,” Anaïs Michel explains. “This can take time and be tricky, but there’s help.”

Public authorities in the EU work together in a network called the Consumer Protection Corporation, which could be crucial in making the implementation successful.

“If there are doubts about understanding and implementing something into law, member states can share knowledge, ask each other, and ask the EU. Still, it is challenging to implement something like this consistently across the EU.”

Gospodinova explains that giving each member state some individual control is important.

“Member states are normally best aware of how its consumers understand things, so it’s important to leave the final touches to each member state.”

However, Gospodinova emphasizes that member states – although they get more control – will still have to comply.

If a member state doesn’t implement it into national law, the EU Commission can take legal action against it. Depending on the outcome, the Court of Justice in Strasbourg can impose financial penalties until it’s done.

The Future of Charging Standards

Gospodinova explains that the EU Commission will assess the innovation and technology situation in three years to determine whether the standard should be updated.

“The legal framework is now in place, so we expect an update to happen swiftly,” she said.

Anaïs Michel takes that statement with a grain of salt.

“The EU Commission estimates it takes about three and a half years to adopt a standard. However, studies by the European Court of Auditors from 2020 show that adopting a new standard takes about seven years.

This happens because so many parties have to be listened to. Stakeholders, experts, businesses, and so on. Striking a balance between considering consumers, the environment, business, and innovation is a very complex challenge,” she explains.