Political and moral dilemma arises as the Faroe Islands hold Parliamentary Elections and extend fishery agreements with Russia amid the invasion of Ukraine. A leading expert believes Faroes can do just as well without it economically, but it may leave the industry and people stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Text, photos, and graphics by Sigurd Skjoldaa Kempf and Anton Dahl Andersen

KLAKSVÍK – “They wanted me to be mayor, but to be frank, I better like working here in my shop.”

Atli Justinussen sells fish and chips on the harborfront in Klaksvík, the second-largest town in the Faroe Islands, a small island nation in the North Atlantic.

The faint sound of engine noise and rhythmic thrumming echoes across the water and blends with the screams of seagulls. The heart of Klaksvík is the harbor. It splits the town in two, and every house is oriented towards its life-giving water.

Justinussen is the deputy mayor and knows the area like the back of his hand – he lost his right hand in an accident when he was two years old. Every summer, tourists flock to his shop to eat the local fish.

“Klaksvík is known as the fishing capital of the Faroe Islands, and a lot of the industry is here, so it’s clear that it means a lot,” Atli Justinussen says.

The Faroe Islands is a self-governing territory but is officially a part of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Faroes have their own parliament, while Denmark controls the country’s foreign policy and defence – but not policies on fishery.

“It’s What We’ve Got”

The country relies heavily on its fishery to keep society functioning for its 53,630 people. In 2021, about 25 % of the fish exported from the islands was sold to Russia.

“It’s what we’ve got,” explains Faroese Hans Ellefsen in his office at the University of the Faroe Islands in Tórshavn, the capital of the Faroe Islands.

Ellefsen has a Ph.D. in economics. His dissertation was on international fishery agreements and their economic importance.

According to Hagstova, the national statistical authority, more than 92 % of the Faroese export is fish.

“We don’t have much of anything else, save for some sheep, so fishery is essential.”

Old Deal, New World Order

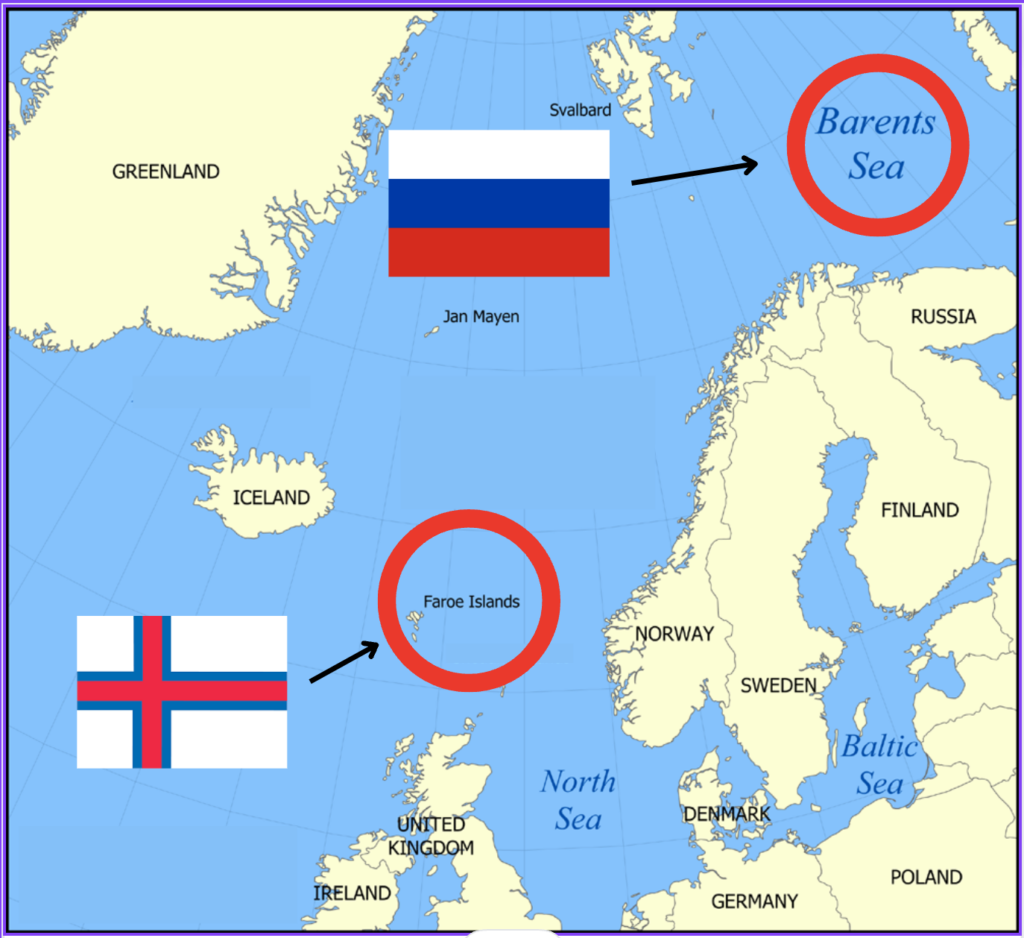

The Faroe Islands and Russia have traded fishing quotas for 45 years, allowing each other to fish in the waters of the other party. The deal allows Faroese fishermen to fish in the Russian part of the Barents Sea, north of Norway and Russia.

The first agreement was signed in 1977, and it has been renegotiated and renewed every year since then, despite Russia being at war multiple times.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, causing a war in Europe, a heated debate has engulfed the political landscape in the Faroe Islands.

The renewal of the deal has been met with criticism from Denmark and other parts of Europe. A Danish member of parliament said the Faroes are “sending a bad signal.”

Criticism from the outside world doesn’t affect the government’s wish to renew the deal.

“I don’t think the criticism is justified – they are not fully informed. The UN says we should continue trading foodstuffs with Russia – just as the EU has kept their exports to Russia about the same since before the invasion,” says Barður á Steig Nielsen, Prime Minister of the Faroe Islands.

According to Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, EU exports of food and live animals to Russia initially dropped as Russia entered Ukraine, but now, they are slightly higher than before the invasion.

The Faroese Government has condemned the Russian aggression in Ukraine, just like Denmark, the EU, and others. The sanctions imposed against Russia are similar here in the middle of the Atlantic to those on the European continent.

Importantly, foodstuffs, such as fish, are exempt from the sanctions imposed by the EU and the Faroe Islands.

“Those sanctions don’t affect us. After all, we’re not selling rockets to the Russians,” Hans Ellefsen emphasises.

What’s the Deal With the Deal?

- In 2023, Faroese fishermen will be allowed to catch 18,461 tons of fish and shrimp in Russian waters

- Russian fishermen will be allowed to catch 92,000 tons of fish in Faroese waters.

- The deal has been in place since 1977 and is renegotiated annually – typically in November or December.

- While it may seem like the deal is better for Russia due to the higher weight of fish allowed in the qouta, the lower price and demand for blue whiting means the actual selling price is about the same for the two countries.

- The value of the fish caught in either Faroese or Russian waters is about 40-53 million euros.

- Foodstuffs, including fish, are exempt from sanctions by the EU and Faroese government.

Fishy Job Security

“Around 250 jobs are directly affected by this agreement,” says Hans Ellefsen.

This number consists of fishermen in the Barents Sea alone. Adding to that are the people employed to process the fish, those keeping the vessels running, packaging, transport, and so on.

If the Faroese government had decided not to renew the deal with Russia, the result would have been unemployment for at least 200 people, according to Hans Ellefsen.

Ellefsen explains that in the short term, many fishermen, relative to the size of the country and industry, will lose their jobs fishing in the Barents Sea. Most of the jobs related to the deal are in Klaksvík, a town of around 5,000 people.

Renew, Reorganize, or Rethink?

Hans Ellefsen suggests that Faroese fishermen could fish in Faroese waters instead of letting the Russians do it.

“It’s a trading of quotas, and the Faroes are perfectly capable of fishing what the Russians are currently hauling out of the water in the Faroe Islands. “

According to Hans Ellefsen, reorganising the fishery is possible, perhaps even in just a few months.

“It wouldn’t take long. You sell one ship and buy another. There might be losses, of course, but it is absolutely doable, and ships are available. They would fare just as well,” he says.

Atli Justinussen disagrees.

“Selling the ships won’t solve the problem. The biggest market and the best price for the fish is still in Russia,” he says.

Ending the deal would result in too many people losing their jobs and the Faroes losing too much money, Justinussen thinks.

“We want to distance ourselves from what Putin is doing in Ukraine, but this is incredibly important for the Faroe Islands as a whole,” he argues.

Hans Ellefsen explains that if the fishing is reorganised to stay in Faroese waters, only about 50 of the approximate 200 jobs will open again.

“Fishing in Faroese waters is more efficient – but this sentiment is not necessarily popular among voters during an election season,” Ellefsen argues.

Ellefsen also highlights the historically low unemployment rate in the Faroes. In September, the unemployment rate was below one percent.

“Those losing their job in the Barents Sea could quickly find another job, but not necessarily the one they desire most. The Faroe Islands constantly lack able-bodied hands as many natives leave the country to study and work in Denmark.”

The Value of the Deal

The potential economic losses of the reorganisation would be on the side of the shipping companies working in the Barents Sea – it wouldn’t affect the Faroese economy as a whole, Ellefsen says.

“If you want to stop the deal, this is the potential price to pay. It’s a small price compared to the price paid by Ukraine,” Ellefsen argues.

To evaluate the ramifications of abandoning a new deal, the Ministry of Fisheries commissioned an expert report. In that, it’s discussed by Ellefsen and two other experts that the value of the deal, looking at the value of the fish caught in either Faroese or Russian waters, amounts to about 300-400 million Danish kroner.

That’s equal to approximately 40-53 million euros.

In other words, it’s slightly below one and a half percent of the Faroese GDP, according to Hagstova, the statistical authority in the Faroe Islands.

While it may seem like the deal is better for Russia due to the higher weight of fish allowed in the quota, the lower price and demand for blue whiting means the actual value is about the same for the two countries.

Election Timing Was No Coincidence

“The timing of the election was no coincidence,” says Hallbera West, an assistant professor of political science at the University of the Faroe Islands.

The sitting Minister of Foreign Affairs was kicked out of the government due to LGBT+ conflicts.

This forced an election to be called at a less-than-optimal time, right when the Russian deal was supposed to be renegotiated. The election was held on December 8th.

However, a leading factor in the election being called was also that the sitting government party, the Union Party, led by the Prime Minister, Bárður á Steig Nielsen, did not want to stand alone with the responsibility of either renewing or terminating the deal with the Russians.

“By establishing a majority for the renewal of the deal right before the people go to vote, the parties neutralize the situation so that not one – but all – are responsible for the renewal,” West explains.

Politicians and decision-makers in the Faroe Islands are divided on how to address the renewal issue.

A few days before the election, Aksel V. Johannesen, former Prime Minister and leader of the Social Democratic Party, the largest opposition party, criticised the current government for not preparing soon enough for a time without a deal.

‘We should have prepared for this, but the government hasn’t. If we become part of the government after the election, we would start preparing – with the industry – for the termination of the agreement in 2024 if the war continues.”

Despite this, Johannesen supports renewing the current deal. The Election results made his party the biggest in Parliament, likely making him the new Prime Minister.

A Sudden Change of Opinion in Parliament

A few weeks ago, the government couldn’t find support in parliament for renewing the deal with Russia. However, this changed after the election was called.

On the final night of debate before Election day, in Klaksvík, Sámal Petur í Grund, leader of the old independence party, aptly named Independence, reiterated his disappointment with the new deal.

“We shouldn’t sell our morals for capital,” he passionately proclaimed as scattered applause filled the main auditorium of the public school in Klaksvík.

They are the only party still against the deal.

Before the election, Independence held one seat in parliament, which meant that the renewed deal had the support of 32 out of 33 members.

However, on Election night, it became clear that Independence lost its only seat.

According to Hallbera West, the party may have attempted to gather support by being the only party opposing the deal.

Because of the election, a couple of parties in the parliament wanted to postpone negotiations until after the elections. Barður á Steig Nielsen, the Prime Minister, says this wasn’t a viable solution.

“I didn’t want to make a deal during an election if only the government parties were involved. Luckily, the opposition reached out and had a change of heart because time was running out on the current deal.”

Silent Companies Planning

The Shipowners of the Faroe Islands, a lobbying organisation representing companies in the Russian part of the Barents Sea, did not want to comment on the issue. The managing director of the organisation, Stefan í Skorini, said:

“As we represent many different interests – including those not fishing in Russian waters – I’m unable to offer opinions on the matter.”

The three shipping companies that own quotas to fish in the Russian part of the Barents Sea didn’t want to comment either.

In the formerly mentioned Ministry expert report, it’s discussed that three new trawlers are currently being built to fish in the Barents Sea.

Their combined value is approximately one billion Danish kroner, which equals about 134 million euros. We wanted to ask the shipping companies what the renewal of the deal means to them and what their plans are for the future, but they refused to comment.

One Step Further

The biggest company in the Faroes, Bakkafrost, has gone a step further than the sanctions forced them to. The company specializes in farmed salmon. Russia used to be their biggest market.

“The deal changes nothing. We haven’t traded with Russia since they invaded Ukraine, and we aren’t planning on resuming trade in the future,” says Poul Andrias Jacobsen, head of marketing at Bakkafrost.

An Easy Target

“We’re an easy target. A small country in the North Atlantic. Other countries say we should stop trading with Russia, but they trade with Russia every day – for billions. It doesn’t make sense,” Justinussen says.

According to Eurostat, the EU exported just below two billion euros worth of food and live animals to Russia between March and September 2022 during the invasion of Ukraine.

“My son is fishing in the Barents Sea. He probably caught some of the fish I’m selling”, says Atli Justinussen as he stands in front of three coolers filled with frozen fish, some of it caught by Gadus, a trawler fishing in the Barents Sea.