In Wake of Historic Fires in Spain: Dropping Population in Rural Galicia Causes Negligence

By Cleo Ding and Gyeongju Hyun

Since July 14th, there have been small blazes in Serra do Courel, a UNESCO-listed scenic forested range in Galicia, northwest Spain. When the fire reached the small village Vilamor in O Courel, it was July 17th.

“The sound of the fire, and the heat were incredible,” said Marta Rodriguez Rio (44), a cow farmer who runs a local tourism business in Vilamor. “The fire went down the road very fast,” she recounted.

.

That day, she hurried home from her translating job only to find her 78 stacks of hay in flames. Her dozens of cows ran to the other side of the mountain. With simultaneous wildfires burning on her farmland, she turned to the goodwill of others to help keep her cows safe.

Ms. Rodriguez said she wished the police would come and help, but they didn’t.

Galicia is one of the regions in Europe with the largest forest mass. In other words, with dry weather conditions it is an ideal environment to start a fire, or several. This fire was caused by a strong storm with 6,000 lightning strikes in less than 4 hours, started in the Courel and went down the slope, threatening to devastate the towns in three days.

The city guard evicted the town residents when the fire occurred. “At first they tried to defend themselves from the fire but it was impossible so they had to be evacuated,” said Matilde Arza, local development agent with the City Council of Folgoso de Courel, one of the main villages in O Courel.

Over the five weeks fighting against extreme forest fires, half of the forest firefighters and many resources such as trucks, planes, helicopters were sent to the burning locations. There was zero help from other autonomous communities or countries.

After 11 days, Guillermo Díaz Aira (53), a volunteer who helped evacuate the rural residents in the fire on July 28th, said they were deeply affected by the fires, but the native forest in Folgoso do Courel survived the fires because the hardwood had endured the blaze.

However, there is a terrible erosion in the soil and the rivers go down full of sediment with the rains now.

Trees in O courel destroyed by the three-day continuous fire. [Photo courtesy @ Galicia Máxica]/[Photo courtesy @ Guillermo Díaz Aira]

Mr. Díaz is a biologist and a mountain guide in Folgoso do Courel, a forest site known for its large pine plantations for timber production. Pine trees are easy to burn and regenerate in a short time.

Last year, Folgoso do Courel suffered from three major large arson fires. The cause has been “foreseeable” no matter by lightning or intentional fire-setting, he added.

“Lack of means of extinction, poor prevention, depopulation, excess planting of pyrophytic species. There are a lot of causes that, together with a terrible drought and a heat wave, have unleashed hell. This land will never be the same.”

— Guillermo Díaz Aira, local mountain guide in Folgoso do Courel

.

He recounted that the most strenuous efforts in the rescue process went to people in the nearby village called Vilar, where people were isolated by the fires without any help.

“The neighbours have been the ones who have saved the villages,” Mr. Díaz said, adding that the local media has failed to reveal the truth: “Everything the press has put out there was sufficient [to prove] that the media is a lie.”

‘Now, instead of green, I see black.’

In the path of the blaze, Vilar is the only populated centre in O Courel where the fire started and the houses are destroyed by the fires.

The village is at the bottom of a slope between Alto do Boi and the Lor River. The entire slope is planted with huge pine trees that are over 20 years old, and some are over 100 years old.

Not a single tree survived. What perished along with the green is the museum of Xan, a cultural heritage of Vilar.

The emergency unit was three days late. They didn’t cross the river to save the villagers in danger, instead, they decided to quell the flames in the forests first. When the unit finally arrived, the village had been ravaged by the blaze and left with burnt-out houses.

Now, out of 15 houses before the fire occurred, there are only two still standing.

Burnt-out houses in Vilar, O Courel [Photo courtesy @ Galicia Máxica]/[Photo courtesy @ Guillermo Díaz Aira]

Only the two families, including Emilio Rio (72), a retired pensionist, and his wife have their permanent residence in town. The other 13 houses were used as a second residence for vacations by emigrants from Vilar.

.

All other houses which were made of wood were burnt down. For Mr. Rio, whose house is made of stones, fortunately there was no major damage to his house because he had a security valve to protect the butane cylinders from further explosions.

Mr. Rio said they did not receive any support from the Spanish government, but the city hall sent water transported on a wagon and help from two neighbours and a volunteer from outside the village.

“The turbine of an airplane”

– Described by Mr. Rio’s wife, as she remembered the horror she felt over the loud noises from the fires.

.

The fire sent huge plumes into the air. Mr. Rio was covering his nose and mouth with a wet towel with his left hand, and trying to put out the fires with a bucket of water with his right hand.

.

The old couple have lived in Vilar their whole life and have no plans on leaving the village.

Mr. Rio’s wife who stands next to him said: “I’m not gonna leave now. What are my alternatives?”

Some villagers have fled to the nearby city called Quiroga, 15 kilometres south of Vilar– a city with a population of around 3,000, which almost dropped by 16% over the last ten years, according to National Statistics Institute.

Alejandro Lopez Lopez (30), Tourism technician of Quiroga’s council said he personally knows a doctor from Vilar who sought refuge from the fires in Quiroga and now he is a local supermarket staff.

Because of the increasing intensity of fires, Mr. Lopez said Quiroga has lost tourists in the past three years.

“I’m not afraid [of being affected by the forest fires]. But maybe in 5, 10 years. It’s possible that this (Quiroga) may disappear. The idea is crazy. But [in reality], no, not really.”

— Alejandro Lopez Lopez (30), Tourism technician of Quiroga’s council

.

50 kilometres west of Vilar, in a city called Monforte de Lemos. Foggy haze encapsulates the city centre which is filled with abandoned buildings. The smell of wood smoke from chimneys drifts through the neighbourhood.

Monforte de Lemos, the second biggest city in the province. According to National Statistics Institute, the city’s population dropped by 6.3% between 2011 and 2021.

Jose Carlos Costoya (60), a railway worker in Monforte de Lemos said the closing of companies and lack of job opportunities are the main reasons for the emptiness.

“There are fewer people working on the now automated railway. It is the lack of work, [which makes] young people go find jobs in other places,” said Mr. Costoya.

With the town emptying, forest management therefore has become less of a priority in rural areas, which are mainly surrounded by forests and mountains.

Urban firefighter David Alvarez (35) in Monforte de Lemos, whose job is to provide water for forest firefighters in the fires, said the lack of surveillance made “the forests not properly cleaned”– with combustible media scattered across the forests.

“So when the fire begins, it’s very easy to grow,” Mr. Alvarez said.

Experts say leaving the forests unattended also causes an imbalance between natural reproduction of trees and human extraction of wood.

“Less wood is extracted. That causes the forest fires to become more and more powerful,” said Raúl de la Calle, the general secretary of the official college of forestry engineers and forestry and natural environment engineers who has worked on fire all his life, adding that the lack of forest management is the fundamental factor in the size of the recent forest fires.

The increasing temperature leads to more dangerous and virulent fires

Pedro Alvarez Redriguez (65), a hunter we talked with in a local pub in Monforte de Lemos, said the 45 houses in his town were not affected because the chestnut trees served as a “natural protection”. However, the landscape in Devesa da Rogueira was affected, which has been categorised as a cultural heritage of Galicia.

According to Xunta de Galicia, the local autonomous government of Galicia, the number of forest fires has declined over the years. About 10,000 wildfires occurred per year from 1990 to 2000, and about 7,000 forest fires from 2000 to 2010. The number goes down to 3,000 per year between 2010 and 2020.

However, the intensity of these fires become dangerous and more virulent.

Unfortunately, Spain has become an environment where the temperature is consistently high and the soil is dry due to climate change.

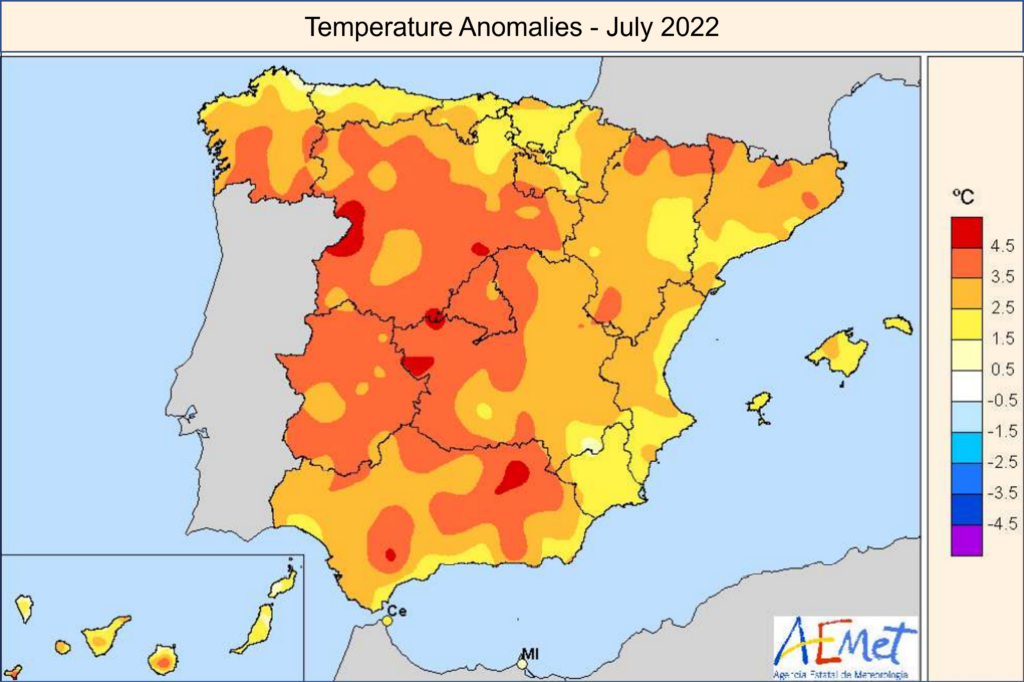

Galicia is one of the states which has been heavily affected by the erratic weather. Temperature this year increased 4 C compared to the average temperature from 1981 to 2010 in southern Galicia, according to a report by the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET) released in 2022.

Severe droughts hit Spain this summer. In the heat wave and dry climate, Spanish forests have become vulnerable to forest fires.

However, the increasing intensity of the new generation of forest fires makes the prediction of forest fires conditions difficult, said Ernesto Rodriguez Camino, a speaker of the new Spanish meteorological association and former head of the Climate Evaluation and Modeling area at the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET).

“In order to accurately predict forest fire conditions, the more data simulation centres in the forest area, the better,” said Mr. Rodriguez.

Mr. Rodriguez believes that the current density of the data simulation centre is not sufficient, adding that there is a lack of funding from the state government.

What do the forest firefighters do in the winter?

“We do not rest in winter, we had not rested in winter. We do preventive work – preparing the territory before the fire season,” said Manuel Martínez Xanquei, senior forest firefighter with Professional Association of Firefighters and Forest Firefighters of Galicia (APROPIGA).

In Galicia, fires are not only concentrated in the summer season, and they tend to be “complex”, Mr. Martínez said.

These ‘off-season’ fires are difficult to predict and generate erratic fire behaviour. “We have gone to a stage, to a level of fires that we had never had in such a massive way in Galicia,” he said, adding that the existing fire season is getting longer.

“The spring months [we have] two to three weeks [of wildfires], and the months of October, November, possibly one more month, there are approximately 40 out of 45 days of high fire danger. But it is not continuous. There is an extension in time.”

The increasing days of increased chances of massive firestorms have created a complicated situation for the rural residents, who in the past, understood how fires worked but are now struggling to adapt to the changes, said Mr. Martínez.

People who set the fires

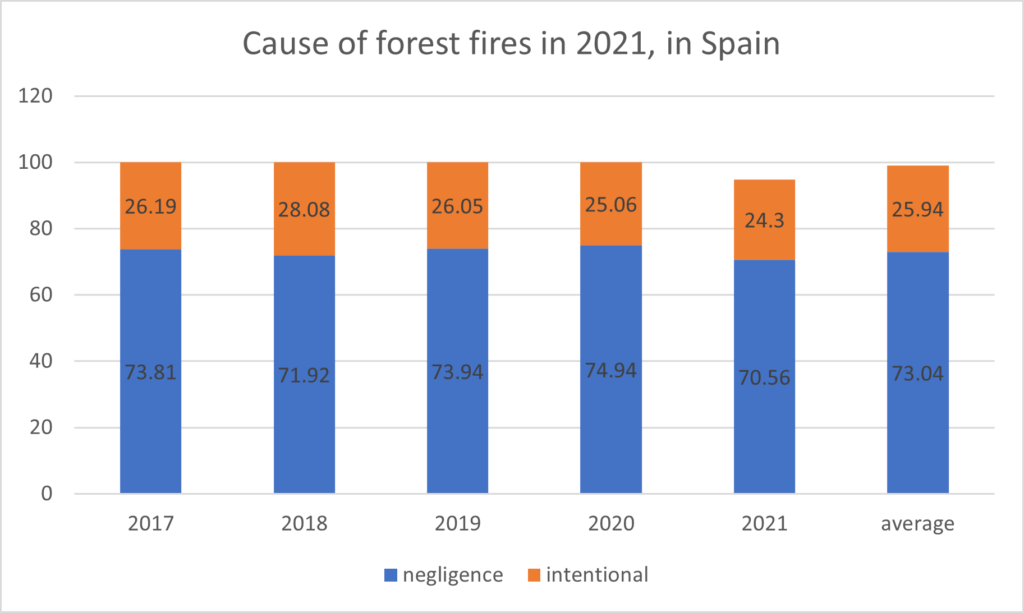

Around 10% of the wildfires are produced by natural causes (lightning) and 2% are reproductions of poorly put out fires. 70% of the fires in Galicia are intentional and 10-15% of the fires are caused by negligence when burning agricultural or forestry remains or accidents involving machinery, said UPA, the National Police Unit in Galicia in an email.

There are various suspected arsonists who benefit economically from the fires including some developers who dream of putting rows of buildings where there were once pine trees, people seeking insurance money, and farmers intending to set unauthorised fires.

Besides the technicians, environmental agents, fire trucks, one of the rescuing efforts belongs to a group of rural firefighters that are employed on a day rate to put out the wildfires. However, the public has a sceptical view on the volunteer firefighters.

“One of the things that people believe here, is that the volunteer firefighters set the fire, they get paid when there is fire,” said pub worker Daniel Perez in Monforte de Lemos (36).

“There is a big difference between clearing up fires when they are caused by human negligence and when they are intentionally produced,” Manuel Ruibal Pena, Head of the National Police Unit in Galicia wrote in an email. “This is because negligence tends to leave more indications and the investigation is not easier.”

Senior forest engineer Raúl de la Calle, however, noted it is “dangerous” to mistake Spain for a country of arsonists.

94% of wildfires were caused by human activities according to the Spanish government’s 2021 forest fire report. However fires set intentionally accounted only for 24%, whereas 70% of the fires were caused by negligence.

“One of the biggest causes is livestock and agricultural practices. Essentially, that practice is burning stubble or bushes to create new pasture, providing crops for livestock, and clearing land for crops,” explained Mr. de la Calle.

Northwestern Spain, such as Galicia, Austrias, León and Zamora, traditionally uses fire for livestock and agricultural practices. This is because fire is a tool with faith that has been used for many years by their ancestors. In particular, fire is maintained a lot in mountainous areas with large numbers of cattle.

In Galicia, where the livestock industry has prospered, fire is used to make cattle pass through, Mr. de la Calle said. A fire is set to remove all the thorny scrub that can impede the cow’s movement, creating a new layer on the surface and giving the cattle a much better environment.

Experts stressed on the importance of education on the use of forest fires and its danger. Especially from an individual’s perspective, for example lighting a barbecue.

Another example of the fire culture in Spain is the increasing use of lanterns as a cultural practice in Catalonia, a region in northeastern Spain, another hotspot for wildfires. These lanterns may fall into the forest and ultimately cause fires.

The investigation and detailed monitoring after a fire occurs

Monitoring activities are also very important for fire prevention. In Galicia, the ministry of agriculture has a Forest Fire Investigation Unit (UIFO), which consists of 15 members of forestry agents. UIFO investigate the causes of forest fires and, if intentional, they conduct a thorough investigation until perpetrators of the crime are found.

In 2021, the investigation unit carried out a total of 242 investigations of different types of arson fires according to Xunta de Galicia.

In addition to Galicia, monitoring activities are also carried out in Catalonia. Sotsinspector of the Corporations of Rural Agents, Gemma Torrelles said the agents spend most of their time in natural areas, monitoring, surveilling, and investigating the risk of forest fire. After observing the natural area, the agents provide this information of the biologics to the local government of Catalonia, followed by a full-scale investigation.

Not all investigations will be able to find the perpetrator, “but the simple fact of stopping by and talking with the local residents where the fire occurred and they see that there is work and monitoring of the events happening, has a great deterrent effect against future fires,” Head of the National Police Unit in Galicia Manuel Ruibal Pena wrote.

Government tries to deal with forest fires, but not enough

The Ministry of Rural Affairs of Xunta de Galicia, the local government of the Galician Region wrote in an email that funds will be invested into prevention infrastructure, fire service resources and so on. 14.8 million euros will be invested in prevention infrastructures by 2023. There will also be more than 20 million euros for forestry, such as establishing and maintaining the forest area or forestry technologies.

Fire service resources will be allocated 14.9 million euros and a new group specialised in fighting large forest fires will be 1.5 million euros.

However, Serafin González, president of the Galician Society of Natural History, pointed out that the government’s fund investment is not enough.

“Galicia has spent the last 32 to 33 years spending a huge amount of funds to put out the fire. However, [the increasing intensity of fires] indicates that fire prevention failed,” he said.

In order to avoid reaching the most avoidable situation, Mr. González believed it is necessary to give aid to people who live in rural areas and discourage them from using the fires.

Miguel, a forest firefighter who works with the Forest Fire Workers Association in Castilian y León (ATIFCYL), raised a strong voice for the government.

“After working hours, I was going to rest at home when my colleague called and said that there had been an accident on my colleague,” he said.

“I was really angry, because we knew this was something that was going to happen because of the situation in the Castilian government,” said Miguel.

“The conditions we are facing are something new. We knew about climate change from years ago and the administration is doing nothing to prepare for climate change.”

Helicopters came to rescue the rural residents trapped in the fires. [Video courtesy @Guillermo Díaz Aira]

Now, forest fires as global issues

“Not only Spain, but also Greece, Turkey, Italy, France, Portugal all are suffering from the forest fires. This is an international issue.” Speaker of the new Spanish meteorological association Mr. Rodriguez said other countries away from Spain or southern Europe share the same concerns.

Mr. Rodriguez sees the climate crisis as a general and long-term problem, so forest fires as a consequence of climate change cannot be solved in a month or even a few years.

Thinklink interactive multimedia about statistics of forest fires’ situations in Southern Europe. [Designed by Gyeongju Hyun].

Mr. Martínez, senior forest firefighter, also believes forest fires are not only Southern European issues.

“In 25 to 30 years, the northern European countries, where they are not used to these temperatures, are not used to this type of fire, can go from Off to ON very quickly.” said Mr. Martínez.

With years of working with the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET), Mr. Rodriguez suggested a solution: Since the countries in Europe cooperate relatively well, they should have an adequate governance structure with high mobility of resources. As an example, the Xunta de Galicia has collaboration agreements in force with the neighbouring country Portugal.

“If our neighbours from Portugal have problems, Spain can send in our fire brigades, our planes, other either human resources or material,” he said.

Mr. Rodriguez believed forest fires are a global problem, but it is still important to manage them at regional and national levels.

He proposed to analyse “the causes of climate change, educate people about the danger of forest fires, manage the forests better, and have an adequate governance structure for fighting forest fires with high mobility.”

“To prevent forest fires, there is no single measure.”

— Ernesto Rodriguez Camino, s speaker of the new Spanish Meteorological Association and former head of the Climate Evaluation and Modeling area at the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET).

.

.

.

We are grateful that this article was produced and finalized in connection with others. Special thanks to our Spanish locals firends and helpful strangers– Emma, Daphne Sacristán, Ander Dacosta, Enrique Nárdiz with Spainfixer, Mr. and Ms. Costoya, and Luis and Estela with the International Press Centre in Galicia, who have supported and championed this feature piece literally every step of the way. From launching us into capable hands of sources, to the tedious and labour-intensive translations, you all have made this article possible.

.

Leave a Reply