By Alessandra Iellamo, Eternity Uwaifo, and Chelsea Alarif

In the Political Guidelines for the European Commission, President Ursula von der Leyen proposed a legal instrument to ensure workers in the European Union a fair minimum wage and ‘a decent living wherever they work’.

In 2022 the European Parliament adopted the proposal guaranteeing an adequate minimum wage for all workers in the EU. The directive aims to improve working conditions creating a decent standard of living.

The directive considers minimum wages to be adequate when they are representative (vis-à-vis) of other workers. The proposal’s guidelines suggest 60% of the median wage or 50% of the average wage as a basis for governments.

By increasing the minimum wage, the European Union hopes to narrow the level of disparity between member states.

The response has varied depending on the strength and bargaining power of trade unions. Some member states have found the directive to be unnecessary, seeing it as a hindrance to their well-functioning workforce.

The effects of the directive remain yet to be seen. Still, the implications of this legislation could be an immense step forward for some economies, alleviating poverty and creating predictability for workers.

Romania

With the third lowest minimum wage in the EU, Romania already has a prevalent level of poverty within its counties. In 2022 85% of all employment contracts awarded are worth less than the threshold for a decent living.

Poverty in Romania: The correlation between statutory minimum wage and poor social conditions.

As winter nears, low earners are forced to take drastic measures to survive the rising cost of living and energy prices. “The people that we work with, the people living on poverty, that experience poverty, are really scared. My colleague Valentin Popa, his family are in the rural area. They are planning to spend the winter in only two rooms, staying together, moving one bed from one room to another,” says Vasi Gafiuc, President of social services provider Bucovina Institute.

With the implementation of the EU’s new legislation, it offers predictability and a higher wage for up to one in six Romanians, yet the directive is still viewed with skepticism.

“Currently, we have a negotiation, but in reality, it is not a negotiation. It’s empty words. In reality, nothing happens. The government on the television say you can buy your basic needs for €175, but they don’t calculate accommodation, only food,” says Razvan Gael, Vice-President of Trade Union SANITAS.

The potential of the directive: An opportunity for a decent living in Romania.

The directive targeting the cost-of-living crisis is set to alleviate the struggle faced by minimum wage workers, increasing the wage to provide a living comparable to the basket of consumption.

“Nearly one-third of people in Romania receive the minimum wage, something that allows you to live at a minimum but above the threshold of poverty. It has to be decent. It has to be an income allowing people to be above poverty,” says MEP Ramona Strugariu.

The directive allows for country autonomy within the bandwidth of the EU. As member states work together, Romania is allowed to revise and adapt its minimum wage every two years under the criteria and rules of the legislation.

“Once you have a pre-set toolkit of rules, clear criteria and procedures to determine this minimum wage, this is something that I think is helpful for everybody,” adds Ms Strugariu.

A running campaign: The clash between the directive and Romania’s 2024 elections.

The timing of the directive interrupts an important period for Romania, its 2024 elections. With the concurrence of the two, the period allows for some of the directive’s criteria to be overshadowed or awash with party politics.

The strength and force of this directive continues to remain in question as Romania implements pensions for heating in rural areas.

“This is not something that should be related to any kind of electoral campaign. It should be part of good governance with or without elections. It should be something that we have to come with in order to simply make people’s lives bearable,” says Ms Strugariu.

Germany

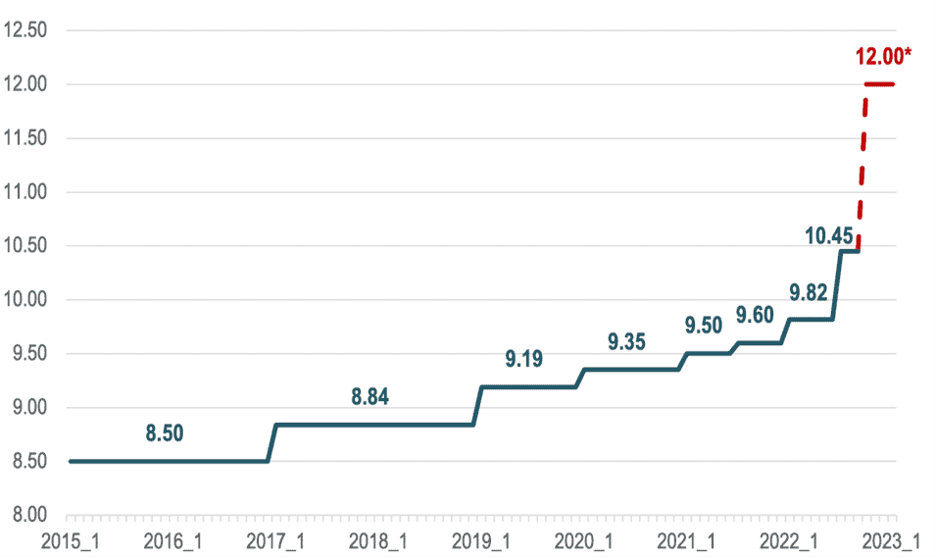

Germany’s introduction of a statutory minimum began in 2015 and progressively increased reaching 12 euros per hour starting October 1 2022.

However, with the continuous and rapid increase of inflation, the set minimum wage has become slightly debatable over the years.

Germany’s perspective on pending EU minimum wage directive

“The German government believes that everything is already contained in our minimum wage law and the minimum wage has been improved this year. We have already realised the aim of the EU directive to reach 60 percent of the medium,” said Friederike Posselt, advisor for tariff coordination at the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB).

The relation between the statutory minimum wage and poverty

With the implementation of a statutory minimum wage set to ensure that all citizens secure their necessities, 15.8 percent of Germans are at risk of poverty. An evaluation of undeclared work in the European Union and its structural determinants conducted by the European Commission showed that 9.3% of total labour input in the private sector in the EU is undeclared.

“We have certain cases where the workers do not get paid the minimum wage and these are fields that should be improved for the workers,” said Posselt. “There are several action plans conducted by the German government to ensure that all workers receive the statutory minimum wage,” she added.

“We know that there are cases of evading the minimum wage by different means, either by unpaid hours or by pretending to be self-employed. The exact number is unknown and is deduced from surveys where the numbers vary,” said Dr. Arne Baumann, head of the Coordination and Information Office at the German Minimum Wage Commission.

“The minimum wage is an instrument against poverty with a very limited effectiveness,” commented Dr. Baumann.

The surveillance of the implementation of minimum wage

“The German customs authorities supervise the minimum wage. Whenever they find a business that pays below the minimum wage, these businesses are fined,” said Dr. Baumann.

“In around 50,000 establishments every year, the German customs authorities practice inspections where 6,700 establishments have been accused of noncompliance with the minimum wage,” he added.

Proportionality between working hours and work intensity

An article published by Oliver Bruttel in the Journal for Labour Market Research highlighted that with the increase of the minimum wage, working hours have been reduced while increasing the work intensity.

“It’s not a general reality, however it happens sometimes. There is some evidence from qualitative studies that this is happening every once in a while. Work intensity has not increased for minimum wage workers overall in the years”, said Dr. Baumann.

This dilemma faces contradictions in surveys and research as employees complain from the increase of work intensity whereas studies reveal the opposite.

“Employees must go to a lawyer or trade union in order to make this clear to the employer that they are paid per hour,” added Posselt.

Denmark

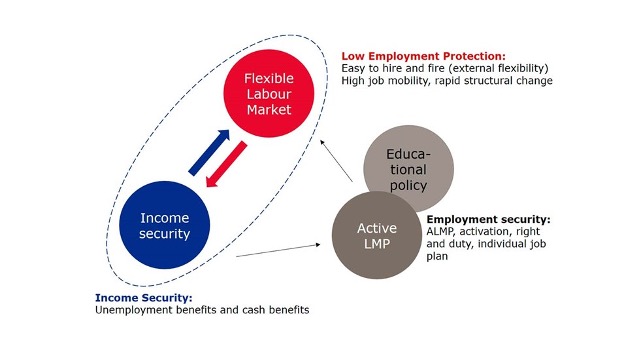

The history of the Danish labour market model dates back to September 5th 1899, with the ‘September Compromise’, the first ever general agreement signed by employers and employees following a strike and subsequent lockout in the summer of 1899. The compromise formed the basis for the Danish labour market we know today, characterized by voluntary agreements between employers and employees.

Unlike other countries in Europe, in Denmark there is no statutory minimum wage. Instead, wages and working conditions are defined in collective agreements (“overenskomster” in Danish) negotiated between ‘social partners’, namely trade unions and employers. These social partners are the ones who negotiate collective agreements according to a system of collective bargaining and regulate employment and working conditions, including wages.

The strong influence of the partners on employment policies, is typical of the Danish labour market and represents a unique feature of the so called ‘Danish model’, which is considered very flexible vis-à-vis European standards, because it combines flexibility and security for the citizens, and tries to reconcile employers’ needs with a flexible workforce and safe working conditions.

A model for other EU member states

“The Danish labour market model has always been deemed as a good example of labour organization, mostly because of the pacific communication between the social partners and a minimal state involvement on the labour market” says Henning Jørgensen, labour market policy advisor and professor at Aalborg University, Denmark.

“The directive is simply not the right tool for Denmark. Of course some wages are very low in many EU countries, but we can’t simply allow the EU to decide our wages, because we risk that in the future it could use this power to demand wage cuts.” he added.

In the OECD Outlook 2018, Denmark came out as the top performer in Earnings Quality. Research findings connect this wage equality with independent, collective bargaining conducted voluntarily by strong social partners.

How would a set minimum wage destabilize Denmark’s labour market?

In Denmark the directive is seen as a hindrance, as this would mean political interference in their national wage-setting systems and a danger for their labour market model.

“The 27 EU Member States have chosen different solutions to labour market regulations, including wage settlement. These choices are rooted in historical traditions, institutions, and practices. Applying a ‘one-size-fits-all solution’ would compromise the Danish labour market ” says Marianne Vind, Danish MEP representing the Social Democratic party.

She added: “A set minimum wage in Denmark would mean a break in the labour market model, more division and even exploitation. It could even cause a vicious downward spiral, as we have unfortunately seen in other countries such as Germany where there is a statutory minimum wage, yet still millions of people live in poverty – despite the fact that many people have one or several jobs”.